Social, sustainable and ESG bonds: where are we now?

European green bond issues are now twice as oversubscribed as ‘regular’ bonds. NatWest Markets’ Dominic Brindley and Dr Arthur Krebbers take stock of the suite of ESG products being used – and what it all means for social housing

Ever since its inception, the bond market has been at the forefront of the most dramatic societal developments – from the Victorian railway bonds, to the early 20th century war bonds, through to the current generation of climate change-oriented green bonds.

The theme seems to be: “If you can finance the issue, you can help solve it.” It is therefore no surprise that the global pandemic has accelerated debt market innovation.

In this article, we will cover some of the key trends and developments, and explain what this means for housing associations (HAs).

Sustainability debt features first emerged in the late 2000s, as European development agencies wanted to more formally link their financing with specific pockets of environmentally targeted projects.

A watershed moment came in 2014 with the launch of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) green bond principles. These set out the voluntary ‘rules’ by which organisations agreed to comply when labelling any bond as green.

Such disclosure components remain true for any use of proceeds impact debt today:

- Use of proceeds: what projects are financed by the bond issue?

- Process for project evaluation and selection: how will the issuer identify eligible impact projects to

be financed? - Management of proceeds: how will the proceeds be handled until full allocation to green projects?

- Reporting: how and when will the issuer report on the projects?

- External review: what is the view of a credible external assurer?

In the years that followed, green debt became a standalone asset class in its own right. Last year saw £285bn of such issuance globally, dominated by sovereigns and agencies (36 per cent), financial institutions (33 per cent) and corporates (31 per cent) – in particular, utilities and real estate. HAs were still a relatively small portion at one per cent.

Yet it is not the only game in town. As more financial market participants embraced sustainable finance, sustainable ‘cousins’ have emerged.

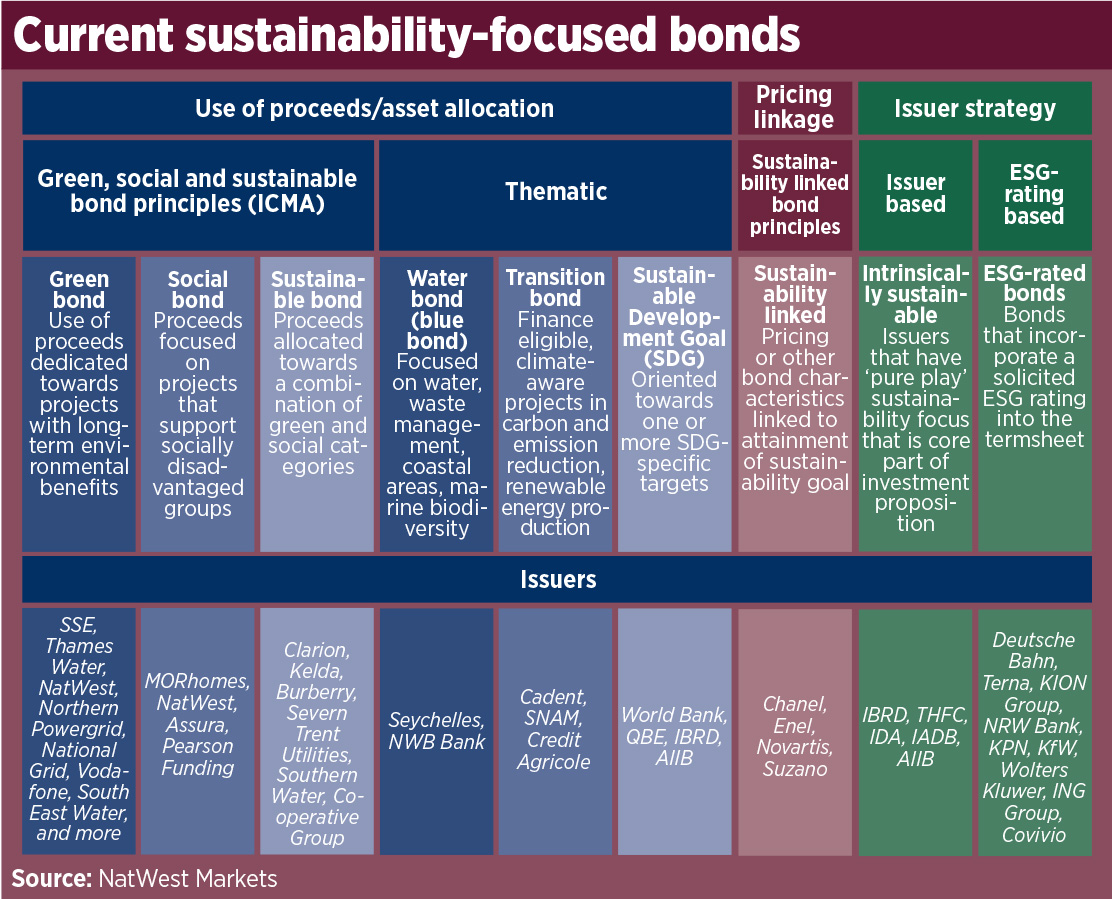

Innovation has taken various forms: new ‘global’ standards such as social bonds and sustainability bonds, sustainability ‘niches’ such as blue bonds and new ways of incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) into debt terms through a sustainability-linked structure (see chart).

Investment rigour has also improved, particularly when assessing issuers. What good is a sustainability bond supporting one per cent of an organisation’s projects when the other 99 per cent is still sub-par?

Hard-nosed economics has supported this trend. As society has become more sustainability-conscious, investors have rapidly followed suit. Circa US$103tn of assets under management (AUM) are currently pledged to the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment, up from US$21tn in 2010. Their appetite for impact bonds means that the average European green bond issue is now around twice as oversubscribed as a comparable conventional bond.

This trend still has some way to go. COVID-19 has added a new sense of urgency to ESG investments and products.

In the second quarter of this year, the average Euro corporate green bond attracted a staggering 47 per cent more demand than a ‘regular’ bond, compared to a 17 per cent stronger demand in the first quarter of the year.

What’s more, primary green debt has also printed at a typical eight basis points tighter new-issue-concession than its plain vanilla counterpart.

COVID-19 has also spawned its own asset class in the form of COVID-19 response bonds, which target medical and economic support. And it has been a powerful force for bond issuers to consider people as well as the planet.

Recent months have seen a range of inaugural sustainability bonds that seek to combine environmentally focused expenditures with those that improve the livelihoods of companies’ more vulnerable stakeholders – be that clients, suppliers, employees or communities. Examples include Pearson and Clarion.

This recognition that the E and S of ESG are interlinked is particularly helpful for HAs. S is very deeply embedded in the sector, while E is at the heart of the net-zero challenge – buildings account for 36 per cent of global energy consumption and nearly four per cent of total CO2 emissions. HAs drafting 30‑year business plans should be actively incorporating their climate change and decarbonisation strategy, particularly with net carbon neutral targets focusing on 2050.

Even if you’re issuing a conventional debt instrument, your end-investors will need to understand your planning on this area – or they will draw their own conclusions. HAs that cannot talk holistically about their sustainability agenda are likely to see their sources of funding slowly dry up.

This does require a common language for ESG between HAs and their capital providers. NatWest is pleased to be working with The Good Economy as lead bank sponsor for the sector-wide white paper on ESG reporting standards. Such unified ESG criteria should help increase efficiency and transparency for the sector and for individual HAs.

HAs wishing to go a step further should consider labelled financing. A social bond is a quick win, formalising many of the disclosure commitments affordable housing providers already make to the regulator and other stakeholders.

One step further would be a sustainability bond. This would enable an HA to formally link its debt financing strategy to its social and environmental ambitions and investments.

Of course, as the chart shows, there are ample other debt structures available. There is a plethora of options – yet, just like with a new building project, it requires careful thought and design.

Dominic Brindley, head of public sector and structured asset finance, NatWest Markets, and Dr Arthur Krebbers, head of sustainable finance, corporates, NatWest Markets

The Impact Investment and ESG Conference is taking place on 15 October. Click here for more information.

RELATED