It’s more than just a housing crisis – it’s a public health crisis, too

Inadequate access to housing carries real and urgent risk to public health. Government must act – starting by returning its focus to the delivery of social rented homes, write Rose Grayston and Miatta Fahnbulleh of the New Economics Foundation

A century ago, under the shadow of another global pandemic and a major war, the Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 kicked off the UK’s first national programme of social housebuilding. It is often forgotten that its architect, Dr Christopher Addison, was not the minister of housing but the minister of health, and that the government’s chief motivation for passing the act was to improve the health of ordinary working people.

The experience of recruiting soldiers and munitions workers for World War I had brought the impact of poor living conditions on the health of the population into sharp relief for politicians. At the time, 90 per cent of families rented from a private landlord. Overcrowding was rampant and ventilation often poor, with millions living in slum conditions.

As the war ended, the ambition to build ‘homes fit for heroes’ was born. In fact, the ambition to address public health concerns has been behind every significant social housing programme in history – from the Victorian philanthropists who started housing associations to tackle urban squalor, to the improved design and space standards in Labour’s council housebuilding programme after World War II, to the Conservatives’ focus on slum clearance in the 1950s and 1960s.

As the country deals with the fall-out from the coronavirus crisis, it is now time to once again learn the vital lesson that good public health relies on good housing for all, and good housing for all cannot be achieved by relying on the market alone. If the need for a new programme of social housing wasn’t clear before, it surely is now.

Coronavirus has made obvious the cost of years of government housing policy focused on allowing the market to deliver ‘just enough’. We have witnessed the scandal of NHS workers faced with eviction in the midst of a national health crisis. For 10 years, support with housing costs through the social security system has been slashed in ways which guaranteed that millions of families would only be able to afford to live in cramped, cold, miserable conditions throughout the pandemic. From 2013, governments allowed office blocks and other buildings to be converted into housing with no space or other quality standards through permitted development rights. As a result, thousands of families have been locked down in converted industrial estates, some in homes with no windows – let alone safe outside space for children to play.

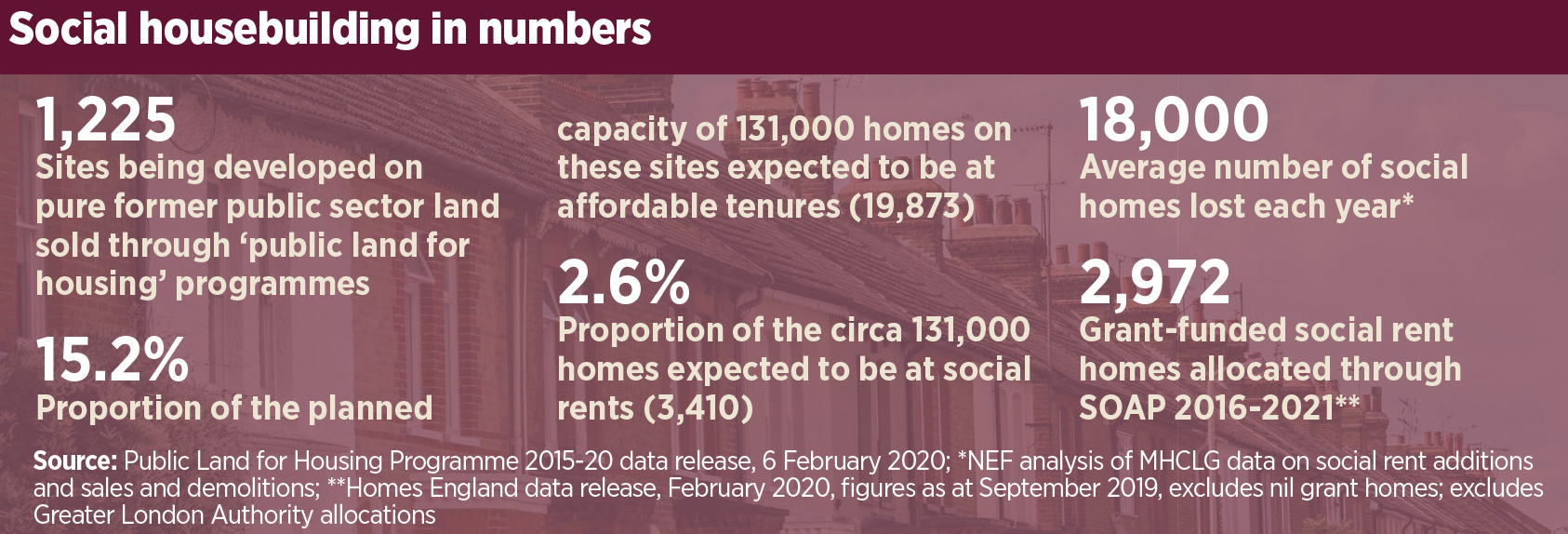

Through it all, the country has sold off social housing faster than it has built it, removing the safety net that should have been there to provide a decent, secure, affordable alternative to these conditions. The past 22 years have seen a net loss of nearly 400,000 social rent homes, analysis of Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) data for social rent additions, sales and demolitions suggests.

Contagious diseases spread more rapidly in overcrowded housing, and it should come as no surprise that communities at the sharp end of the housing crisis are among those hardest hit by COVID-19. Higher rates of overcrowding among Black and ethnic minority households provide part of the explanation for the disproportionate impact of the virus on these groups.

But the consequences of bad housing for the UK’s experience of coronavirus go far beyond the practical challenges of self-isolating in an overcrowded home. Poorly designed homes and inadequate housing security are having a profound impact on many people’s mental health and ability to work and study through the pandemic.

Research from Place Alliance estimates that 10.7 million people in the UK felt uncomfortable at home during the first national lockdown – whether because of a lack of indoor or outside space, poor access to parks in the local area, or a lack of community in places dominated by high-churn private rented housing. People living in newer homes had the worst experiences of lockdown, an indication of just how far housing standards have been allowed to fall.

In a world in which pandemics may become more common, tolerating further declines in housing standards carries real and urgent risks for public health, worker productivity, educational attainment and social mobility. Instead, we must see good housing as part of our civic immune system.

There are some early signs the government may understand this, having taken steps to introduce space and natural light standards to those permitted development conversions. But far more wide-reaching action is now needed.

First, the government must follow through on its commitment to end Section 21 no-fault evictions. Second, it should ensure that the income shock caused by the pandemic does not lead to greater housing insecurity, by controlling rents for those affected and dealing with the growing issue of arrears.

Above all, the government must commit to increasing annual net supply of social rented housing – a commitment conspicuously absent from the recent Social Housing White Paper, despite a loss of 17,000 social rent homes in England last year. Building social rent is the tried and tested way of delivering homes to higher quality, security and affordability specifications than can be achieved through the market alone – at scale, at pace and for all. This means giving local authorities, housing associations, community land trusts and other social housing providers the tools they need to play their full part in driving up social housing supply in the coming months and years.

It means changing the way we use public land to increase the delivery of social rented homes – from the pitiful rate of 2.6 per cent seen in recent years – as well as broader land market reform. It means investment in grant for social rent homes across the country.

We have already lost out on thousands of homes, including social homes, which would otherwise have been delivered this year, because of the immediate impacts of the pandemic. There is no more time to lose.

Rose Grayston, senior associate - land and housing, and Miatta Fahnbulleh, chief executive, New Economics Foundation

Hear from Miatta Fahnbulleh on day two of the Social Housing Annual Conference on 1-3 December.

RELATED