UK housing performance over 30 years: a time of expansion

John Perry explores the progress of housing associations since the 1980s

Social Housing magazine was a child of its time. Created in 1988 just as housing associations’ access to private finance was formalised, it was there both to report on what was happening and to provide guidance to everyone involved. It was a time of expansion.

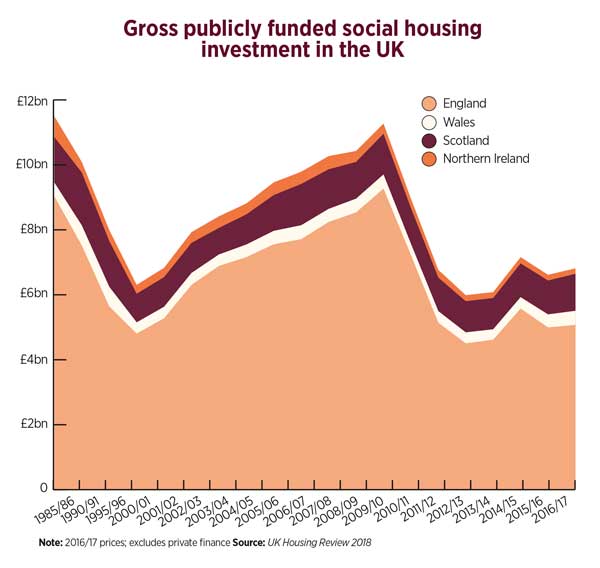

By 1990, Housing Corporation investment reached £1bn for the first time and associations built more than 20,000 new homes. Five years later their building peaked across the UK, with almost 39,000 units completed. In 1998, Chiltern District Council was a pioneer in a process which would lead to 1.3 million council dwellings transferring to associations in England using private finance, eventually accounting for half of associations’ stock in both England and Scotland.

It’s a common misconception that the Thatcher government stopped building council houses, but only in 1993 did output fall below 5,000 annually across the UK, a figure never again exceeded despite a recent modest revival in England and a stronger one in Scotland.

However, in 1989 the finances of the two parts of the sector separated decisively. While associations had freer access to private finance, council housing was forced into a ‘redistributive’ subsidy system, creating a further incentive to transfer stock for councils who saw much of their rental income go to the Treasury.

The housing association boom did not last long. Spending cuts started to reduce output to a new low in 2002/03. New Labour focused its early attention on the poor state of council housing, which had a backlog of almost £20bn of disrepair.

Investment was accompanied by measures giving tenants more choice, setting performance targets and incentivising councils to set up ALMOs to manage their stock if it was not transferred. Tenant groups, often opposed to what they saw as market-driven reforms, successfully campaigned against transfers in Birmingham, Camden, Edinburgh and elsewhere.

Eventually, Labour began to increase investment in new build, as supply was falling well behind demand and homelessness peaked across Britain in 2003. Yvette Cooper’s 2007 green paper set a target of delivering three million new homes by 2020 and led to three years of higher social housing investment. Long-standing moves to reform council housing finance also took shape, although implementation was delayed by the 2010 election. Output of affordable housing (broadly defined) climbed back to more than 50,000 units per year.

Taking ownership

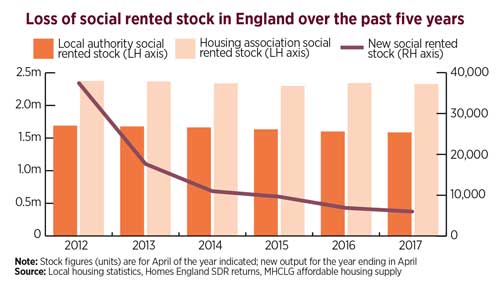

Since the early 2000s, owner-occupation had been falling while private renting grew. The global financial crisis then brought a nosedive in private sector output, and the coalition and Conservative governments from 2010 shifted their focus away from social housing investment towards the private sector. Remaining support focused on development at higher, ‘affordable’ rents that required lower grant levels, while building for social rent rapidly declined.

Housing associations’ new priorities caused tensions about how to meet growing homelessness needs.

Funding to meet the Decent Homes Standard was halted, leading many to feel that, after a short renaissance, council housing was again in decline. The Grenfell Tower fire last year seemed to symbolise a growing neglect of council housing and its tenants.

The opposition and the sector itself recognised the significance of Grenfell and called for more investment, especially for social rent.

Recent history

The post-referendum government has indeed made significant changes: the Affordable Homes Programme’s short-term switch to shared ownership was replaced by renewed emphasis on rented homes, with some provision for social rent.

Policies seen as an attack on council housing – such as the enforced sale of high-value homes and the ending of so-called ‘lifetime’ tenancies – were dropped. Extending the Right to Buy to housing association tenants looks like it might not pass the pilot stage.

A new rent settlement promises a more secure income stream to social landlords after April 2020. And one of the sector’s long-standing demands – to remove the caps on borrowing for new council housing – has now been met.

Will this be enough to secure a step change in delivery? While output will increase, there is still a huge gap to be closed, especially if new homes are to be genuinely affordable to low-income working families. Incremental changes have raised the government’s total investment to more than £9bn in the period to 2020/21, plus whatever extra borrowing councils now take on. However, in real terms this is still less than half the investment levels when Labour left office in 2010.

Overall housing investment in terms of grant, loans or guarantees in the period to 2020/21 will be about £54bn following the recent Budget. Nearly four-fifths of this still goes towards propping up homeownership and the private market.

Only a decisive shift in priorities towards housing for those who can’t afford homeownership will create the breakthrough that is still required.

After 30 years, Social Housing still has a vital task in helping to hold the government to account.

John Perry, policy advisor, Chartered Institute of Housing

- This article is based on one in the Chartered Institute of Housing’s publication, the UK Housing Review 2018. The 2019 edition will be available in March

Thirty years of Social Housing magazine

This week, Social Housing has published a series of articles and reflections on the housing sector to mark the magazine's 30th anniversary:

Turning a page

Luke Cross reflects on Social Housing past and present, as the magazine celebrates 30 years as the go-to publication for social housing finance.

Looking back:

UK housing performance over 30 years: a time of expansion

John Perry explores the progress of housing associations since the 1980s.

30 years of change as a constant

Julian Ashby looks back at how UK housing has performed over the past three decades.

Looking ahead to the next 30 years:

Bigger, better and still socially driven

Kate Henderson looks ahead to the future of housing associations.

Resilience means creating places people want to live

Associations’ unique blend of social mission with organisational scale, flexibility and professional excellence makes them primed to meet the housing needs of the future, writes Zafrin Khan-Wheatley.

Housing should be more than a financial asset

Tackling the housing crisis will mean reducing the speculative demand for housing as a financial asset rather than a place to live, writes Josh Ryan-Collins.

RELATED