How does UK social housing compare with European markets from a credit perspective?

Robyn Wilson finds out how UK social housing’s credit and investment profile compares with different markets in Europe

The social housing sectors across many European countries are linked through one striking similarity: decreased public investment.

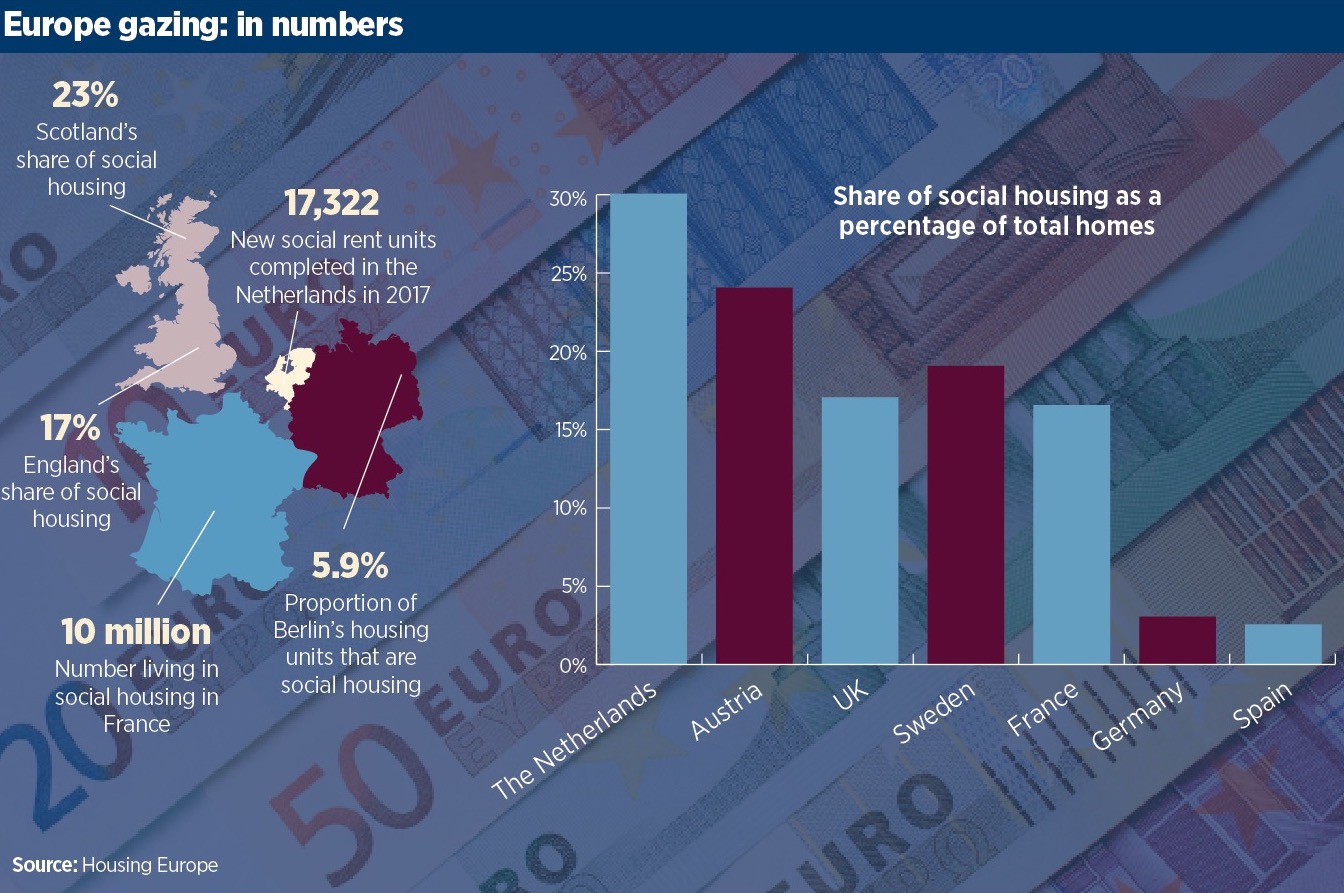

According to Housing Europe – a network of 43,000 providers – total public expenditure on housing development in the EU declined by 44 per cent over just six years, from €48.2bn in 2009 to €27.5bn in 2015.

This notable drop in public funding has prompted a number of housing providers across Europe to seek private investment in recent years as they struggle to meet an ever-growing demand to build more social and affordable homes.

At the same time, an investment opportunity has been presented, particularly for US firms. Towards the end of 2018, an interest rate gap began to widen between the US and the EU – more than two per cent (US) compared with a zero per cent lock (EU) – making the EU an altogether more attractive proposition.

Maria Goroh, director at Centrus, says: “Investors in the US became more active in social housing in the past two to three years, with at least five to six new entrants who started investing in social housing debt.

“[It] is still largely the insurers who are investing in the debt to match their liabilities, so they are attracted by stable cash flows and the highly rated nature of the sector, which have quite transparent rating methodologies.”

This shift was coupled with a growing awareness among global investors around the social housing sector. As Anthony Marriott, head of treasury at Peabody, explains: “It takes a while for an investor to look at a sector, get comfortable with it and understand a bit about it.

“But they realise the social housing sector is regulated and that most of the funding deals they’ve done are on a secured basis. It’s a steady investment, it’s not a fantastically exciting one – you’re not going to make massive returns, but it will be steady over a period of time.”

So as the sector increasingly becomes an attractive place to invest, what makes the English market stand out? And how does it compare with some of its European neighbours that are also very much in need of capital to grow?

“It takes a while for an investor to look at a sector, get comfortable with it and understand a bit about it”

England

England’s substantial development-for-sale activity is fairly unique in a European context, with a higher number of English housing associations (HAs) exposing themselves to the for-sale market to cross-subsidise their social housing delivery.

This exposure has been widely acknowledged by credit ratings agencies – including Moody’s, which warned in March of the credit risk posed by growing sales activity.

But grant via Homes England also plays a role in how English HAs fund their housing delivery, while funds raised from the capital markets saw a significant increase last year, according to the Regulator of Social Housing’s 2018 global accounts report.

It showed that 48 bond issues or private placements took place in the year in total, compared with 26 in 2017 and 23 in 2016. These raised a combined £4.9bn for the year, compared with £2.6bn in 2017 and £1.7bn in 2016.

Deal flow has included a wave of US private placements, new foreign bank entrants such as National Australia Bank and First Abu Dhabi Bank, and a £150m finance deal between Peabody and the European Investment Bank (EIB), the latter of which has invested more than £4bn in UK social housing to date.

On Peabody’s deal, Mr Marriott says the English social housing market is a good investment proposition for a number of reasons, including getting “a clear bang for your buck”.

He says: “Most HAs borrow to develop and the EIB will only fund the social housing portion of the development, so they give you money and you have to spend it on new homes for social housing or improve your existing social housing stock. The benefit from them is very clear.”

The English social housing market is a good investment proposition for a number of reasons, including getting “a clear bang for your buck”

France

In contrast, finance for social housing in the French market comes predominantly from the public lender (the Caisse des Dépôts), which makes up around 80 to 90 per cent of funding, according to Elise Savoye, senior credit analyst at Moody’s in Paris.

Describing France’s social housing sector outlook as currently stable, Ms Savoye says: “The regulatory framework is very strong and all the French housing associations have access to dedicated funding. Most of the French HAs do not go to the market – they go to the Caisse des Dépôts.”

Christophe Parisot, managing director at Fitch, who is also based in Paris, says that social housing providers have typically borrowed through the Caisse des Dépôts because of its “affordable-rate, long-term loans”, although he adds that this is starting to change.

“Recently, social housing providers have tried to diversify their funding sources through the capital markets due to the higher loan rates seen through the Caisse des Dépôts.”

This chimes with Ms Savoye’s view. She says that while the public lender “will remain the largest lender by far”, more French HAs are looking towards the capital markets to raise funds.

“We have a major player that has recently tapped the market. It’s called Action Logement and it’s a group of many French HAs; it’s by far the biggest group. The market share of Action Logement in terms of units under management is 18 per cent of the French social housing sector.

“They have publicly said they want to grow more with the market and take advantage of the low interest rate environment, so we’re expecting that bigger HAs will grow with the private market.”

In terms of risk profile, Fitch rates its French providers in the single A category, which is about the same as the UK, says Mr Parisot.

He adds: “In France, the key characteristic of the borrowers is they are quite high leverage because they have benefited less than the English HAs from capital grants, although they have benefited more from a very easy access to loans from the banks, especially through the Caisse des Dépôts schemes.”

The Netherlands

The Netherlands, meanwhile, has a set of financial and policy structures that create a slightly different profile from an investor and credit perspective.

With one of the largest social housing markets in the whole of Europe (30 per cent), homes are funded through a government-backed fund known as the Guarantee Fund for Social Housing (WSW). The WSW provides guarantees to lenders granting loans to HAs for social housing projects and other properties with a social or public function. These guarantees then enable housing associations to borrow on favourable terms.

WSW was set up in the 1980s to guarantee loans for housing improvements and later was extended to all housing loans. Characteristically it has a solid security structure, and the guarantees it provides are very highly regarded.

It is this, coupled with the country’s much stricter policy environment, that makes its credit profile different from the likes of the UK, says Jeanne Harrison, vice-president and senior analyst at Moody’s.

“They don’t provide grant funding for the development, but they try to ensure the interest costs are low to make it easy for [providers] to borrow and fund their development”

“A key distinction from a credit perspective in the Netherlands is that the government ultimately backs the vast majority of its debt through WSW. That guarantees housing associations’ borrowing and then the Dutch central government guarantees the WSW, so the fact the vast majority of their borrowing is ultimately guaranteed by a triple A-rated government makes their credit profile very different.”

Again, in contrast to the UK, the Netherlands’ policy environment is much stricter, after a scandal involving its largest social housing provider, Vestia. The Dutch HA had to be rescued by the government in 2012 when it came close to bankruptcy after losing €2.5bn in a derivatives deal.

Ms Harrison says: “[Following this] government passed legislation that really de-risked the HAs. That limited the kind of activities that HAs could get involved in so the policy environment over there is quite different – they don’t encourage the cross-subsidy model that we see in the UK.”

Karin Erlander, director of international public finance ratings at Standard & Poor’s, says the one rating the agency has in the Netherlands, for Stichting Stadgenoot, is its highest at AA.

“They’ve gone through an asset management programme where they’ve demolished a lot of non-performing assets and also aligned their portfolio more towards the [government] guidelines,” she says.

“The debt is guaranteed by WSW. WSW is rated AAA, which means that the interest rates are quite low. So they don’t provide grant funding for the development, but they try to ensure the interest costs are low to make it easy for [providers] to borrow and fund their development.”

Germany

Cross over to Germany and the social housing sector is comparatively very small (with a three per cent share) but this is because homes are essentially delivered by the private sector at lower rates.

The private rented sector accounts for nearly 80 per cent of Germany’s rental market and about 44 per cent of its total housing market, according to academic journal Critical Housing Analysis. State subsidies, rent ceilings and occupancy commitments are then applied to some of the dwellings.

As Stefan Kofner, a professor of housing and real estate, writes in a research paper in the publication: “Referring to ownership structures does not make sense in the German case, since around three-fifths of the social rental housing stock have private owners.

“The private owners have been able to build up these social housing stocks either by applying for public funding for their housing projects or by taking over public or factory-related housing companies, including their social housing stock.”

Although it is a mature market, one problem with Germany’s social housing stock is that its state-subsidised homes return to the mainstream market after about 30 years. After this, they are rented out at market rent or sold on, which is creating a demand-side gap for these homes. To put that into context, between 2017 and 2020 the long-term rent controls will expire for 43,000 social rent apartments each year, according to Housing Europe.

From an investment perspective, Berlin-based Lutz Rittig, managing director at Ritterwald consultants, says the country remains an attractive proposition. “In Germany, there is currently a negative yield on 10 or 30-year bonds, so a lot of investors say the next safe haven investment is real estate, so there is a huge demand on real estate.

“People come to Germany because it’s big and within Europe it’s too big to fail. There are non-German investors who for the first time are interested in the German real estate market to park their money in a safe haven.”

“An investor is always looking for a stable political climate”

Southern EU member states

Looking to the southern EU countries, the investment landscape is once again very different. Amsterdam-based Ad Hereijgers, business development director at Ritterwald, says that the social housing markets are perhaps less desirable from an investment perspective.

“If you go more south, to Italy or Spain, and to some extent Portugal, you get a completely different tenure. The majority is owner occupancy and a smaller part is rental. But the part that is rental has relatively low rents, with a lot of government control.”

He adds: “An investor is always looking for a stable political climate, at least if you are talking about investments in residential real estate and involvement in the long term such as pension funds, which

invest for 15 to 20 years.

“They don’t mind regulation as long as they can count on it but what an investor doesn’t like is instability and the more south you go, the more vulnerable it gets.”

Elsewhere and more broadly across Europe, there appears to be one area where the EU is ahead of the game compared with its English counterpart, and that is sustainability.

This has been brought to the fore as the investment community becomes increasingly focused on environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment.

Ms Goroh cites the recently announced sector initiative, in which Centrus and Peabody are lead partners, to develop an approach to measuring ESG in social housing.

Ritterwald has also been working in this area, launching a new ‘Certified Sustainable Housing Label’ to help providers attract capital from impact investment.

In November, Clarion became the first English HA to secure the label. German landlord Gewobag and French landlord Vilogia have also been awarded the label.

Still, Piers Williamson, chief executive of The Housing Finance Corporation, says the UK is “playing catch-up” in this space.

He says UK building regulations are nowhere near as tight in terms of sustainability as the EU. “So, EU funds when they’re looking – and it’s mainly EU funds that are big on ESG – most of them are not investing in the UK, so there’s a demarcation.”

That said, he believes change is coming in England, prompted by a government consultation on the Future Homes Standard, which includes proposals to increase the energy efficiency requirements for new homes in 2020.

In addition, changes brought into force this October by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) have placed more pressure on pension funds to set out their ESG policies, Mr Williamson says.

“I think we’re being dragged into an ESG world. UK funds are probably going to become more insistent – the DWP has just changed the rules. So, we might see it domestically, and that over time might encourage more EU funds into the UK.”

RELATED