Development after the pandemic

From COVID-19-related delays, to planning changes and energy efficiency – what do the current challenges mean for housing associations’ development pipelines? James Wilmore reports

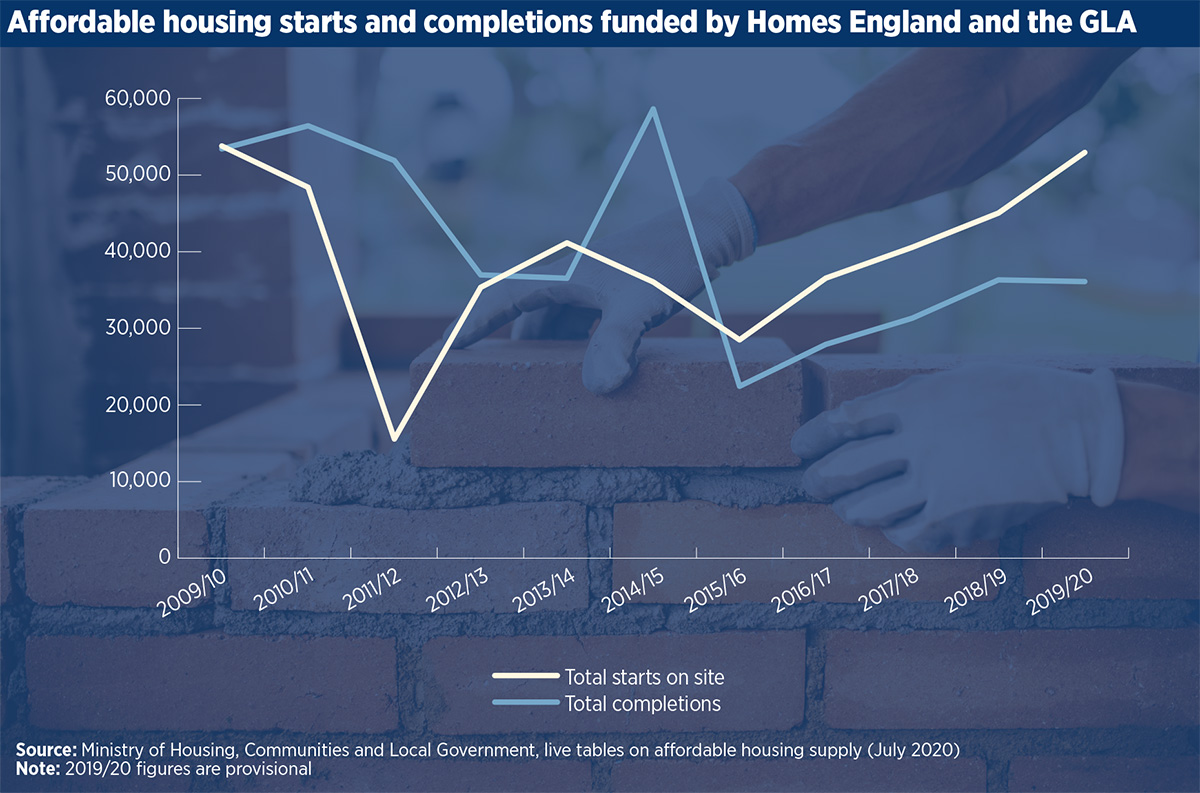

Boris Johnson’s post-lockdown mantra of “build, build, build” arrived in the aftermath of a severe hit to UK construction, including within social housing. As the pandemic struck, the vast majority of housebuilding sites shuddered to a halt.

Even before the crisis, social landlords were grappling with a host of challenges that were denting bottom lines and development ambitions. Building safety reforms, a promised planning shake-up, a push towards zero carbon and Brexit made up an already weighty list. Add COVID-19 to this, and the pressure has ramped up significantly.

A slew of financial updates in recent weeks has given a snapshot of the impact of the pandemic so far.

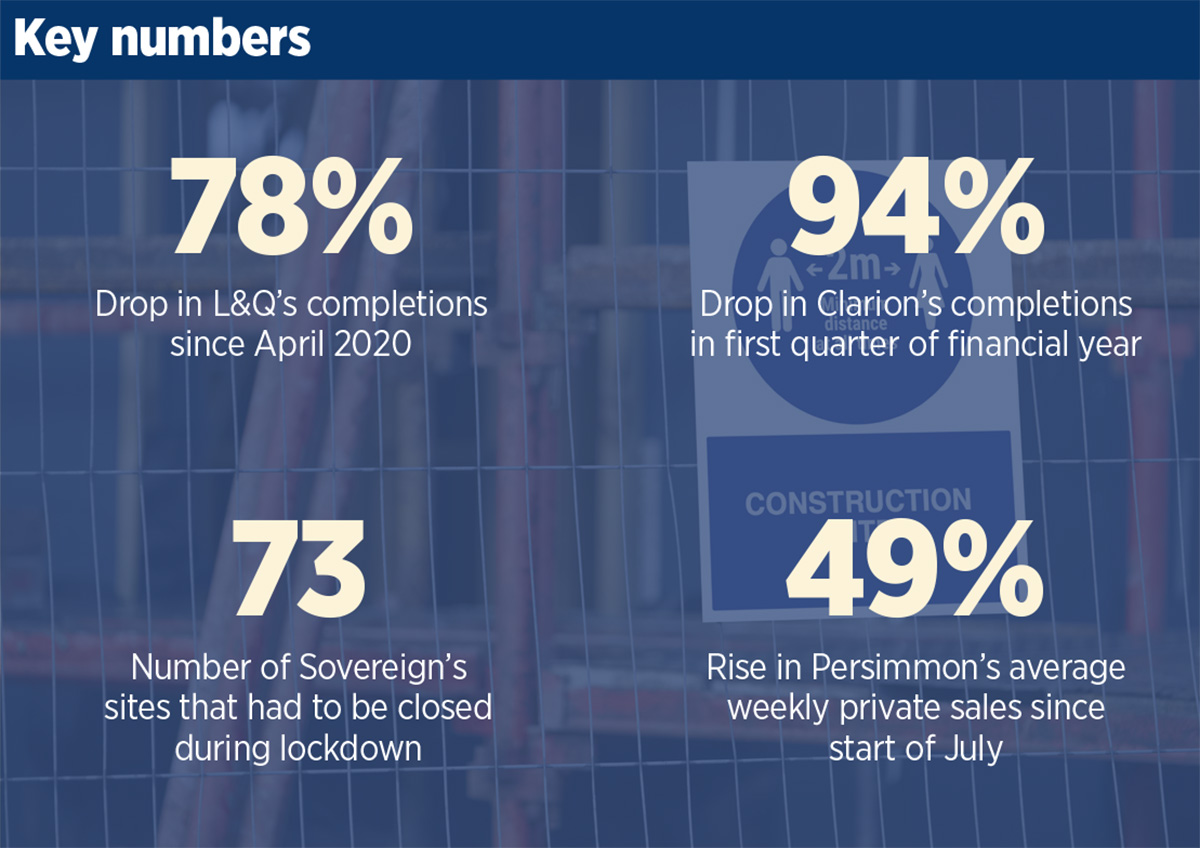

Large London landlord L&Q reported a 78 per cent drop in completions since April. Fellow G15 association and the UK’s biggest social housing provider, Clarion, saw its starts dive 94 per cent in the first quarter of the new financial year. Sovereign, meanwhile, said its target of 1,900 homes a year had been hit by the lockdown.

“This year is effectively an enforced blip,” Steve Aleppo, finance director of investment and commercial at Sovereign, tells Social Housing.

But could this “blip” drag on for the sector? Let’s first look in more detail at the impact on construction sites and the housing market.

Sovereign, which manages 60,000 homes across the South of England, saw the closure during lockdown of 73 of the 83 sites where it was either contracted to acquire homes or planning to build new ones. The association is particularly reliant on developers as around 85 per cent of its new homes come from Section 106 agreements.

“Many developers are having to adapt to new site safety measures, which means their productivity levels are slightly below what they are used to,” Mr Aleppo says.

Steve Trenwith, land and planning director at Sovereign, adds: “The story we keep hearing is they’re around 70 per cent [capacity].”

Jonathan Layzell, executive director of development at 32,500-home Stonewater, has heard similar things. “Because they are adopting safer methods of working, some of them are saying it will slow the speed at which they can build,” he says.

But the impact is not all negative, he adds. Some developers and contractors have reported that having a rigid timetable where sub-contractors can be on site only for a set amount of time due to social distancing means jobs are done quicker. “They’re not giving the trades the flexibility to take a day-and-a-half when they think it should take one,” Mr Layzell says.

But, as housebuilding gets back to some sort of normality, concerns remain about the state of the housing market with the UK now officially in recession. Commentators have predicted a fall in values of anything up to 20 per cent.

And with many associations exposed to the open market, as noted in recent rating updates by credit agencies, this is worrying.

For the time being, however, the housing market appears to be holding up. Nigel Wilson, chief executive of Sunderland-based Gentoo and chair of Homes for the North, says the pent-up demand seen throughout lockdown and the boost from the stamp duty holiday means that reservations and sales are “sustaining reasonably well”.

But he remains cautious. “You don’t want to be too optimistic,” he says.

At L&Q, Waqar Ahmed, group finance director, says it has yet to see a drop in house prices. “If anything they’ve gone up slightly,” he says.

The positive comments chime with an update from house builder Persimmon in August which revealed that since the start of July it had seen a 49 per cent jump in average weekly private sales.

However, for housing associations exposed to commercial sales, would changing tenures on future developments be a possible solution? Many seem to be waiting to see what happens to the market first.

Mr Layzell says Stonewater has not changed its approach to tenure. But he adds: “We are looking at the impact [of switching] if there’s a lack of money in the mortgage market.”

With mortgage lenders tightening up their criteria for borrowers, it looks like this pressure could take hold. As Helen Collins, head of Savills Affordable Housing Consultancy, says: “We are already seeing a pulling-back

from [consumer] lenders.”

Aside from COVID-19, associations have plenty of other threats to their development pipelines – not least, the proposed scrapping of Section 106. In its place, as set out under the government’s proposed planning reforms, would be a new national flat rate charge in the form of an infrastructure levy. Ministers have claimed that the new system would deliver more affordable housing, but many are sceptical.

Shelter argues that social housing could face “extinction if the government removes the requirement for developers to build it”.

The National Housing Federation points out that Section 106 is the “single biggest contribution to building new affordable homes in the country” and last year helped to deliver around half of all affordable homes.

Mr Wilson stresses the importance of making sure there are safeguards. “We need to make sure ministers understand the consequences of their desire to change,” he adds.

While this particular reform will be some time off, another more immediate change is raising concern. The Planning White Paper proposes that the threshold for developers being required to deliver affordable housing on small sites is raised from 10-home schemes to 40 or 50-home sites.

Ms Collins says: “It’s a real worry, particularly in rural areas where a local authority might be very keen on providing more affordable housing. There is a lot of activity on sub-50-unit sites right across the country.”

Looking further ahead, another factor weighing on minds in the sector is the UK’s push towards net-zero carbon. While the need to achieve this is clear, some are uneasy about the costs involved.

Phil Elvy, executive director of finance at 19,000-home Great Places, which operates across the North West and Yorkshire, is concerned about the financial hit from retrofitting homes.

“A lot of our properties are terraced, where any carbon solution is going to be incredibly expensive,” he says. “If that costs a lot more than we’ve already factored in to our business plan, then something’s got to give.”

The government has so far announced £50m of funding for social housing as part of a wider £3bn green investment package. But Mr Elvy says this is a tiny proportion of the necessary long-term spend. “It’s a drop in the ocean compared to the cost of achieving zero carbon,” he says. “Fifty million will probably do a couple of thousand houses.

“Zero carbon will affect virtually every single one of our properties. We don’t yet know how much it’s going to cost, how easy it is to do, how practical it is to do, and what the options are.

“We’re talking about a massive scale here and it may be development that has to compensate for it.”

Mr Wilson agrees on the size of the challenge. “The numbers that have been crunched by various organisations will be eye-watering,” he says. “We will need to have a very grown-up conversation about how we manage that against all the other pressures and demands we have.”

A turn to modular?

One of the overarching narratives about the pandemic is the idea that it has sped up the inevitable. In the housing sector, some believe that the crisis could boost the take-up of modular housing.

Phil Elvy, executive director of finance at Great Places, says: “If you can build a home in a factory and do that in a socially distanced way more effectively, then that might nudge that to happen more quickly.

“[Offsite] has always been more effective, but the gap [between modern methods of construction and traditional housebuilding] might have got bigger.”

Great Places has just started its first offsite scheme in Blackburn for 16 homes. Mr Elvy adds: “We’ve nothing at scale yet but I’m sure it will come.”

Waqar Ahmed, group finance director at L&Q, says: “A shift to modern methods of construction where you can apply social distancing measures and ensure a diverse workforce – I see that as an opportunity to accelerate investment.”

The group has already vowed to deliver all of its new build homes using some form of modern methods of construction by 2025.

Meanwhile, L&Q’s Mr Ahmed says: “The problem is replacing all your gas appliances with electrical appliances by 2050. In L&Q’s case, with 100,000 homes that cost is going to be in the billions.”

In the meantime, the more pressing issue for housing associations has been making sure their buildings are safe in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire.

A new building safety regime beckons, but many have already taken action to fix their most at-risk blocks.

Nevertheless, the costs are still mounting as the focus turns to buildings other than high rises. For larger landlords the costs are vast and could have an impact on development pipelines.

Clarion has said it plans to spend £100m over the next five years on fire safety in its homes – on top of the £50m it has already spent. Fellow G15 landlord Optivo has set aside £80m for fire safety work over the next six years. As a result, Paul Hackett, chief executive of Optivo, said that the association will be forced to make some “difficult choices”.

L&Q announced a year ago that it was putting a pause on new development projects, including buying land, partly due to Brexit uncertainty, but also as a result of escalating fire safety costs.

But Mr Ahmed is keen to stress that the provisions are there for fire safety works and that they will not affect the building of new homes.

“The impact on development has already happened,” he says. “Whatever we need in the next 10 years has been fully provided for in the budget, which is about £40m a year [for fire safety].”

Outside the capital, in pockets of high rises in urban centres such as Manchester, the impact of fire safety costs has been smaller. As Savills’ Ms Collins says: “It’s manageable and shouldn’t have a significant effect on development.”

Beyond this, looming in the background, is the nagging threat of a no-deal Brexit, which could add further to the sector’s headaches.

Despite all this, associations are retaining a positive tone when it comes to their long-term ambitions. L&Q has a stated aim of delivering 100,000 new homes over the next 10 years – announced four years ago, but for which it has said 2019/20 is year one.

Mr Ahmed says the group is sticking to that number. “There are factors that will impact on the pace that we deliver them but what won’t change is our 100,000 target,” he says. “This year we will be behind target on completions but next year there is no reason why we shouldn’t outperform.”

Mr Aleppo at Sovereign says that the association is making “cautious” assumptions around completions in this financial year.

Nevertheless, he is confident that things will bounce back next year. “From 2021/22 onwards we are assuming that we will return to delivering 1,900 homes a year.”

Ms Collins has also been impressed by how the sector has navigated the bumpy waters caused by COVID-19 so far.

“Generally the sector is in a pretty good place financially, in terms of liquidity,” she says. “Organisations will obviously be watching the housing market as furlough starts to unwind, but so far so good.”

But Mr Layzell at Stonewater adds a word of warning: “We are still quite early on in terms of the economic impact of COVID-19.”

Housing associations are generally regarded as counter-cyclical, meaning they would be shielded from the worst excess of a financial downturn thanks to grant funding and government-backed income.

But as many housing associations continue to lay themselves bare to the whims of the open market, the ability to deliver planned development programmes – and the government’s 300,000 homes a year target – may yet be sorely tested.

RELATED