A new chapter for council housing?

From the top council for affordable homes delivery in England, to the largest local authority landlord in Scotland, Colin Marrs finds out how two councils are addressing local need

Cornwall Council

Cornwall has consistently been among the top local authorities in England for the delivery of affordable housing, and in 2017/18 it topped the chart with 912 affordable homes. In a top 10 that contained three London boroughs and growth areas in Cambridge and Thurrock, rural Cornwall’s presence may be surprising. But there is good reason for the high levels of delivery, according to Jon Lloyd-Owen, housing service director at Cornwall Council.

“Many of the pressures we have in Cornwall are the same as other local authorities across the country, but they articulate themselves differently down here,” he says. “The pre-eminent issue is one of affordability. We have relatively high house prices and rents compared to local wages. The multiple between average wages and house prices is comparable with the situation in London and the South East.”

However, the picture varies within the county. “The affordability gap is more acute in coastal areas,” Mr Lloyd-Owen says. “A high demand for second homes and holiday lets mean both house prices and rents are higher in these popular areas but wages for local people don’t respond accordingly.”

Cornwall’s local plan, adopted in 2016, provides for 52,500 new homes up to 2030. The majority of these are set to be delivered by private developers, and the council’s plan aims to ensure that their schemes boost affordable housing. Overall, the target in the local plan is that 30 per cent of private schemes should be provided as affordable, with a further five per cent provided as custom build.

However, the target takes into account the varying house prices within the county. The plan created five zones based on house prices. Developments within the highest-value zone are expected to provide 50 per cent affordable, while the affordable requirement within the lowest-value zone is just 25 per cent.

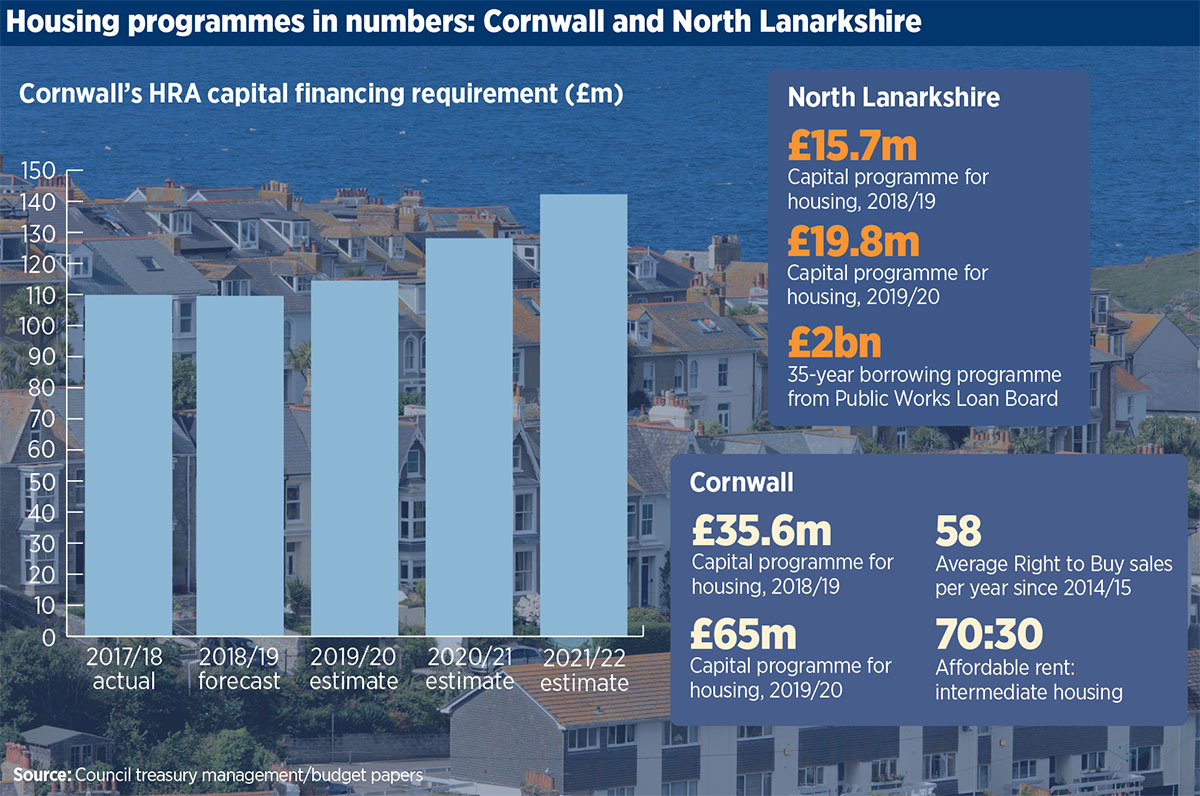

The council is the largest affordable housing provider in the county. It owns 10,300 homes through an ALMO, the vast majority of which are provided at social rent levels. Mr Lloyd-Owen says that spending through the council’s Housing Revenue Account (HRA) needs to take account of the needs to maintain these homes, but that the government’s lifting of the HRA borrowing cap has provided new opportunities to increase its development programme.

“We already had plans in train to start building again and use up our remaining headroom when government made the announcement that it would lift the cap. When that happened, we increased the planned homes from 150 to 350 homes by 2023. We are now working on an even more ambitious business plan which could increase this number to more than 1,000.”

Homes delivered through the HRA have so far almost exclusively been let at social rent levels, but Mr Lloyd-Owen says that the council is looking at whether it should include different affordable products, such as shared ownership, in the future development programme.

The danger of losing the new properties through the Right to Buy is a concern, but not a barrier, according to Mr Lloyd-Owen. “Practically, the cost floor provision [allowing councils to recoup build and maintenance costs] means we can’t be required to sell homes for less than they cost to build for 15 years. That provides some financial reassurance.”

In 2016, in a separate strand, outside the HRA, the council took the decision to intervene in the private rented sector (PRS). The scheme aims to provide 1,000 homes in the county’s large settlements.

“We aim to set an example in terms of private market rented provision,” he says. “One in five people in Cornwall lives in PRS housing and the quality varies wildly. We are keen to drive up the quality of products and provide more secure five-year tenancies.”

The council has already completed the first pilot across two sites in Bodmin and Tolvaddon. Between them, the sites provide 50 homes at open market rent, 26 at affordable rent, 22 for open market sale and 15 for shared ownership. The schemes were paid for through the council’s general fund but will be transferred to the council’s standalone investment company. Future homes will be delivered through and held within the company.

Mr Lloyd-Owen also stresses the strong relationship that the council has with housing associations in the county. “This is partly because three of them – Penwith Housing Association, Coastline Housing and Ocean Housing Group – were created from large-scale voluntary stock transfers from our predecessor district councils.”

The council also provides grants directly to housing associations. The money comes from the council’s capital programme, as well as from making use of Right to Buy receipts. The scheme has provided around £14m over the past three years, and has been extended for another three. Housing associations come forward with schemes and the council considers them.

Mr Lloyd-Owen says the scheme allows the council to complement the grant funding provided to associations by government agency Homes England. “Homes England had a particular focus on shared ownership. Our focus was on rented products. So we have the ability to balance changes in national policy,” he says.

In addition, the council is able to require grant recipients to buy units required through Section 106 agreements on other schemes, and to provide sprinkler systems in new homes.”

In addition, the authority convenes a housing group, bringing together all providers to discuss strategic issues relating to housing provision. “The relationship isn’t just about development and grant funding,” he says. “Registered providers are seen by councillors as a genuine partner.”

Mr Lloyd-Owen says that the current arrangements mean the council has not considered creating a local housing company model. “We haven’t seen the need – our investment programme and the lifting of the HRA cap have removed any drivers there might have been even further.”

Cornwall: key numbers

10,317

Number of units

£109.6m

Debt

£502.7m

Total assets

£71.20

Average rent

Source: Social Housing May special report/councils’ 2018 returns for HRA borrowing

North Lanarkshire Council

With 37,000 homes in its ownership, North Lanarkshire Council is the largest local authority landlord in Scotland. A number of Glasgow’s suburbs sit within the council’s boundaries, as well as the new town of Cumbernauld. The council is currently embarking on an ambitious programme that will see it replace much of its housing stock, as well as increasing the amount of affordable housing.

More than 12,000 households are currently on the council’s housing waiting list, according to Pamela Humphries, head of planning and regeneration at the council. However, the diversity of the area means that pressures vary considerably from place to place. “In some areas we have quite a lot of stock and a high turnover, whereas in some areas where there is a lot less stock and lower turnover – such as Cumbernauld – the pressure is much higher,” she says.

In May last year, North Lanarkshire councillors voted to demolish all 48 of its high-rise tower blocks. Over the next 20 years, the authority intends to demolish 4,000 flats through the programme. The council’s broad-brush assumptions estimate that around half of the flats (2,300) will be replaced on the cleared sites and adjacent land.

The towers were all built between 1965 and 1973 and all had cladding systems installed between 1973 and 1985, although the council does not make a direct link between the programme of demolitions and its response to the Grenfell Tower tragedy. The council says the aim is to ensure all blocks are energy efficient and attractive to current and future tenants, and improve the health and well-being of residents. The first phase, which will see the demolition of 1,600 flats, is earmarked to take six years.

In some parts of North Lanarkshire, the re-provisioning programme will have a significant effect on reshaping the built environment. Almost 60 per cent of the council’s tower stock lies within Motherwell, where tower blocks account for nearly 40 per cent of all council stock. In Coatbridge, towers account for around a third of all homes owned by the council.

Another strand of the council’s affordable housing strategy is to build 2,150 new homes by 2027 across its area. The authority is looking to develop on sites in its ownership, including a number of former schools. “On some of the sites we are looking at building mixed-tenure communities, which we believe will help from a placemaking point of view,” Ms Humphries says.

Much of the funding for the new homes will be sourced from the More Homes grant stream made available by the Scottish government to support its ambition of delivering at least 50,000 affordable homes by 2021. “We agree a broad five-year programme with the government, which enables us to plan for a longer period,” Ms Humphries says.

However, the council faces high build costs, and Ms Humphries estimates that the £59,000 per home available through Scottish government grants covers only around a third of the construction costs. “A lot of our sites are brownfield and in former mining communities so the costs of remediation can mount up,” she says. “In addition, we are very focused on regeneration so we sometimes need to spend a bit more money on small sites, so won’t be getting the economies of scale that a large house builder will get on a greenfield site. That is a choice we are happy to make.”

Ms Humphries says the push by the Scottish government to increase the rate of housebuilding has also had the unintended consequence of pushing tender prices up. “There is a high demand for skilled labour and contractor capacity is limited, while everyone is now trying to develop at the same time,” she says.

To make up the remainder of the funding required, the council has agreed a 35-year programme of £2bn borrowing from the Treasury’s Public Works Loan Board. “We hadn’t been building since the 1970s so the HRA had no debt on it previously, so we are in a good position,” Ms Humphries says. Borrowing will be repaid from rental receipts received from residents – the council last year agreed annual rent rises of five per cent each year up to 2021/22.

To bring the number of additional HRA homes through the investment programme up to 5,000, the council is also planning to buy back 550 homes that were previously sold through the Right to Buy programme. Ms Humphries says that the move will help make it easier to do common works on blocks where the majority of flats are still in council ownership. “We currently can’t force leaseholders to contribute unless blocks are in very bad condition, which means tenants are missing out,” she says.

Ms Humphries says that, at an average purchase price of around £70,000, the exercise is providing good value for money. “We bought around 130 last year when they came on the market, and are on track to do the same amount this year. Compared to buying other properties on the market, former council homes are much better value for money.”

The council’s plans to increase its housing output are intended to complement rather than displace activity by housing associations, Ms Humphries says. “One of our roles is to draw up a local housing strategy for the area. We identify our priorities and then discuss projects proposed by housing associations that can help us meet those.”

One example of co-operation Ms Humphries points to is a recent scheme in which the council used its compulsory purchase powers to acquire land and transfer it to housing association Sanctuary. The move allowed the demolition of an existing block and a multi-storey car park, which has been replaced by 136 flats for social rent.

At the moment, the council does not feel the need to create a local housing company, while it is focused on council housing. However Ms Humphries says the model may be adopted in future if the council looks at mid-market rental properties, for people on a lower income but who do not qualify for social housing.

“We want to attract workers to the area and there is a quality gap in that market at the moment. If we did that we would do it through a company, as City of Edinburgh Council has done. But we have enough challenges to deliver our current plans at the moment.”

North Lanarkshire: key numbers

12,000

Households on council waiting list

48

Tower blocks to be demolished (4,600 homes)

5,000

Homes targeted in housebuilding programme to 2035

RELATED