Best price, guaranteed

Social Housing reports on the final stages of the existing Affordable Homes Guarantees Programme as Chancellor Philip Hammond signals further market interventions

The Affordable Homes Guarantees Programme (AHGP) is arguably the most successful scheme of its kind.

More than £3.2bn of funding – representing about 92 per cent of the £3.5bn of UK government guarantees made available for affordable housing four years ago – will have been lent to 64 housing associations by March 2018.

AHGP financing will have supported more than 28,000 homes, along with regeneration projects and various forms of community care.

That places it well ahead of any comparable market interventions. Its ‘sister’ programme, the £3.5bn Private Rented Sector Housing Guarantee Scheme (PRSHGS), has seen just £265m issued.

The closest to AHGP in deployment terms is the £50bn UK Export Finance guarantee scheme, which has seen 36 per cent put to work.

There has been £1.8bn of infrastructure deals signed under the £40bn UK Guarantees Scheme – albeit with more prequalified – which was last year extended to 2026 and will now include a construction phase. Under the more controversial £12bn Help to Buy scheme, £2.3bn of guarantees were issued.

But while launched – notably by the coalition government – to a fanfare of housing minister support, political posturing around the AHGP has dwindled over the years, and the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) this month declined to comment on its performance.

The announcement in the Autumn Budget of £8bn of new guarantees for housing seems to have offered a chink of light, with confirmation that some could “possibly” be used for affordable housing.

And with AHGP and PRSHGS announced in 2012 as part of a £10bn housing guarantee, there was £3bn on reserve and “subject to demand” – which could in theory be allocated without the government having to pass the legislation it requires to issue new guarantees.

Beginnings

For Piers Williamson, chief executive of Affordable Housing Finance (AHF) – the government delivery partner and subsidiary of long-standing bond aggregator The Housing Finance Corporation (THFC) – the AHGP has been “by many measures the most successful government-guaranteed borrowing programme in the UK”.

He points out that AHF has been able to consistently deliver sub-two per cent bond issuances across the portfolio of loans, which will be managed to 2044.

“By the end of the programme, the average saving on the full £3.2bn programme for participating associations is 1.3 per cent per annum: that is a lifetime interest saving of circa £1bn,” says Mr Williamson.

Already a customer of THFC, it was the European Investment Bank (EIB) that finally got AHGP under way after a slow start, with a £500m loan facility in January 2014.

“Being able to factor in that cost of borrowing makes all the schemes stack up better.”

Andy Howarth, Fortis Living

Mr Williamson says: “In retrospect it took EIB funding to get AHF going. We were in a new space with government – helping them form their risk appetite and at the same time encouraging associations to try a new concept.”

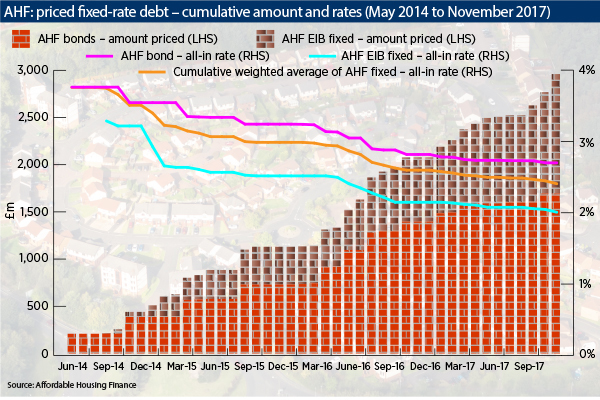

The graph (see above) shows £2.96bn of fixed rate deals done by AHF to date. The structure sees the government ‘double guarantee’ the debt, underwriting the loans AHF makes to the registered provider (RP) borrowers, and the bond or EIB borrowing by AHF.

Bond investors and EIB get a ‘clean’ government guarantee. Whitehall takes comfort that the debt should never be called, as any problems would be sorted out at the individual borrower loan guarantee level.

Following the 2015 Autumn Budget – and the clear focus on homeownership which is still prevalent in housing policy two years on – March 2016 was confirmed as the last date for new applications. Many expected the government to extend the scheme, with one rumour that it was only the late submission of paperwork that had stopped it moving ahead.

Pros and cons

Despite the record-low rates on offer and a range of housing association borrowers, many of the biggest names in the sector opted not to use the AHGP. Some have suggested the process was too onerous, while others were put off by the fact that it was available for new build only, not for refinancing.

Large developing associations were uncomfortable with the lack of MV-T valuation methodology, while there was initially a higher EUV-SH rate, which came down to more standard levels in March 2015.

Despite the decline of the UK’s AAA sovereign rating, downward trajectory of associations’ ratings and volatile policy environment, appetite has “remained steady”, according to Fenella Edge, treasurer at THFC.

“Most AHF bond investors view this as an alternative to gilts with a spread pick-up, so their appetite has remained steady throughout the period. In terms of spreads over gilts for bond issuance we have seen the tightest pricing in recent times – so post-Brexit referendum and post-sovereign downgrade.”

She adds the fact that both EIB direct funding and the guarantee scheme are not available for refinancing has meant RPs continued to access the bond and PP markets, “albeit not in the volumes they might have done otherwise”.

But there have been some questions about the central driver for AHGP: to what extent the cheaper borrowing has delivered homes that would otherwise not have been built.

Phil Jenkins, partner at Centrus, says in terms of access to funding, AHGP is “the most successful private finance model in the UK, with no evidence of market failure”.

But he adds that a “back-of-an-envelope” calculation shows that a 100 basis points saving on the £3.5bn programme translates into £35m per annum across a sector which in 2016 generated total surpluses of £3.3bn after interest costs of £2.9bn.

Using an indicative ‘economic subsidy’ of £100,000 per rented home, that would pay for an additional 350 houses per annum over and above what the sector might anyway deliver.

“Even if the entire £8bn earmarked for loan guarantees was used for AHF Mark Two, the additionality would only amount to around 800 units per annum,” he says.

Ms Edge counters: “I am not sure that is the right way to look at it. It is not how many houses you could build with the interest savings – but how much additional borrowing you could take based on those interest savings... You could borrow more for the same interest cost and with that additional borrowing you could build more homes.”

For example, she says, if the interest saving across the programme is 100bps – so around £32m per annum – and assuming the cost of new debt is 3.25 per cent – that £32m per year would support around £1bn of additional debt at market rates.

“That would fund a lot more homes – 6,000 plus.”

Andy Howarth, executive finance director at Fortis Living, agrees that it doesn’t simply come down to the number of homes, and is more about what the cheap debt enables borrowers to do.

Through various EIB and bond tranches, Fortis has borrowed £140m of long-dated AHGP debt at an all-in cost of just 2.66 per cent.

He says: “Being able to factor in that cost of borrowing makes all the schemes stack up better than they did previously. It really does help to have more certainty of cost on long-term funding.”

He adds that for smaller associations in particular, this enhancement of viability could be the element that enables them to develop schemes they otherwise could not.

“When we formed Fortis Living in 2014 we agreed a strategic target of 500 new homes per year.

The AHF programme matched our development objectives, and the £140m we have drawn has been utilised in the delivery of 1,604 new units; 1,233 rent and 371 shared ownership.”

Mr Williamson adds: “Even if no more business is to occur under the AHGP, a legacy has certainly been established, one that is sure to influence financing models in the future.”

What next?

But where do guarantees leave the government balance sheet?

The National Audit Office’s (NAO) 2016 report – ‘Evaluating the Government Balance Sheet: Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Guarantees’ – puts them in the context of stimulating growth and addressing market failures.

The most significant guarantee schemes represent more than £100bn in potential government liabilities should the guarantees all be taken up. The upside is that the guarantees do not require any initial outlay, but “generate income for the government in the form of fees paid to compensate it for the risk taken on”, the report says. They do not impact the government’s debt unless the guarantee is called upon.

But the NAO report points out that guarantees tie the repayment of loans in the housing and infrastructure sectors directly to the public finances and could crystallise “at once in the event of a major shock to the economy, such as another financial crisis”.

While not announcing the large-scale capital borrowing programme many were wishing for, chancellor Philip Hammond announced plans in November for another £8bn of guarantees to support private housebuilding and the purpose-built private rented sector.

The DCLG has said that “the new guarantees” will potentially be used for affordable rented housing.

The latest interpretation from a spokesperson was that the £8bn “will be used to deliver rented housing and to support borrowing by smaller-scale builders”.

“We will be in a position to say more in the coming months,” he said.

RELATED