Feature: stock market movement

Ten years on from the launch of the stock rationalisation toolkit, Robyn Wilson explores what is driving disposals across the sector

The Housing Corporation, predecessor to Homes England and the Regulator of Social Housing, launched its stock rationalisation toolkit in 2008 to help housing associations drive efficiencies and value for money across their organisations.

Ten years on and stock rationalisation has evolved into much more of a boardroom agenda, as associations look for new ways to develop and grow as funding streams fluctuate.

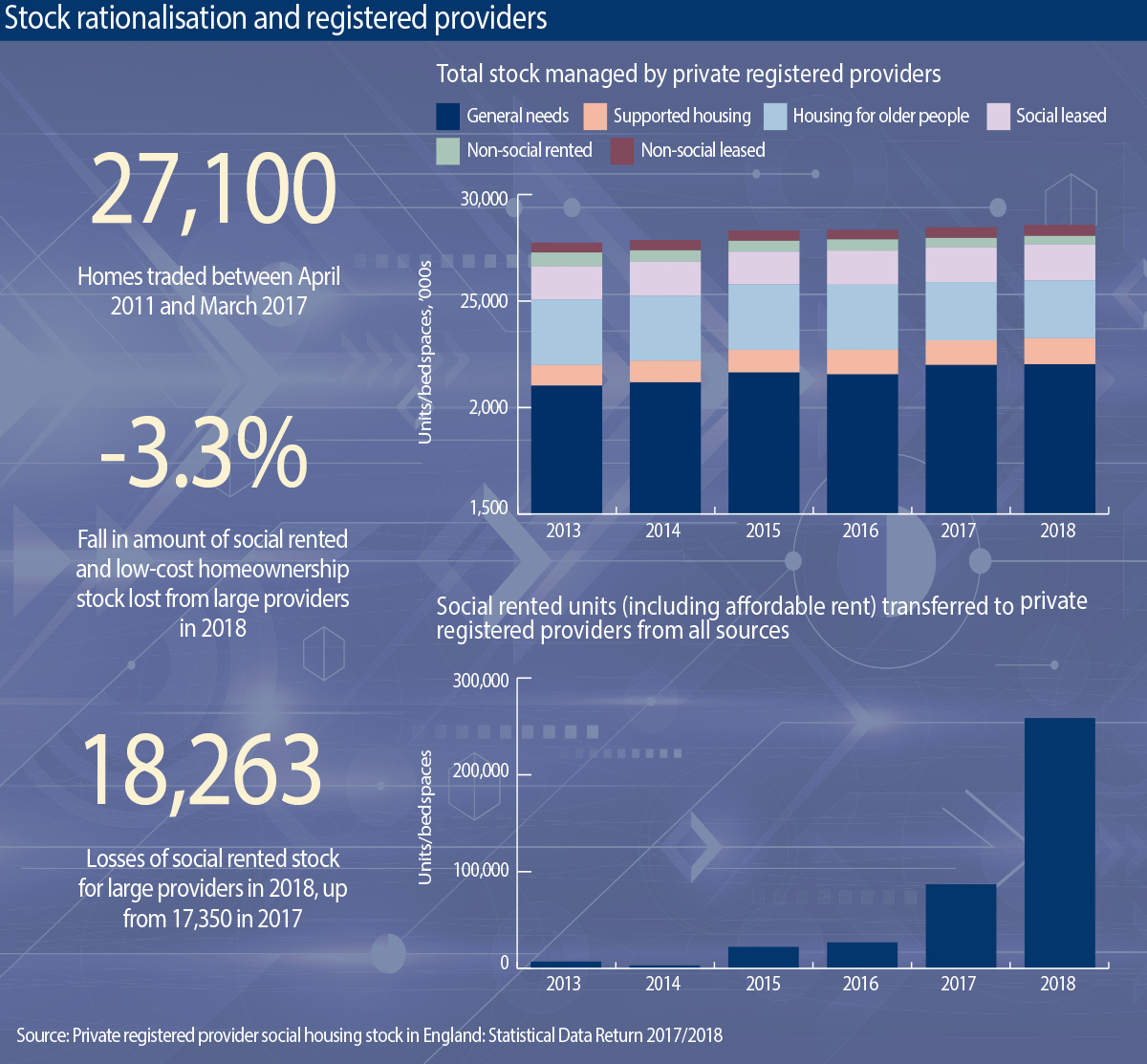

With total trading figures remaining relatively low, however – just 27,100 homes were traded between April 2011 and March 2017 – there may well be more stock movement to come. Meanwhile new entrants, trends and pricing models promise to shake up the stock rationalisation landscape.

Development

For Helen Collins, head of Savills Housing Consultancy, who recently authored a report on the stock rationalisation market, development ambitions will continue to be a key driver.

“Housing associations have been stepping up over the past few years to build more homes, and particularly now, selling tenanted portfolios to raise money to support development,” she says.

This can be seen with some of the larger players in the market, including the UK’s biggest provider, Clarion Housing Group, which plans to churn up to one per cent of its social stock each year, “accessing capacity” of other associations through strategic disposals.

Another large provider, Guinness Partnership, has already built stock rationalisation into its ‘Destination 2018’ business strategy, which overall delivered £12m of cost savings, according to its 2017/18 accounts.

Catriona Simons, the group’s chief executive, tells Social Housing that as well as being a significant way to increase the geographical coherence and improve efficiency in an association’s service, stock rationalisation “importantly enables the redeployment of capital around the sector so we invest more in new supply”.

This point is echoed by the association’s director of asset and growth strategy Kevin Williams, who adds: “Stock rationalisation allows us to invest in building more homes for those in housing need and concentrate our resources in the areas where we can be most effective.”

For smaller organisations that don’t want to take on development risk, however, the stock rationalisation market offers an attractive alternative, says Simon Vevers, strategic assets and partnerships director at Hyde Group.

“We may well sell a number of homes where the buyer is most likely to be a smaller housing association that has decided that development risk isn’t really within their appetite. So, they grow through the purchase of tenanted stock, of which they benefit from a day one rental fee,” he says.

Seat at the table

A significant player in the market, Hyde has purchased 1,800 properties over the past three years and sold more than 3,300. Mr Vevers says its stock rationalisation programme has also seen the group reduce its number of local authority areas to 43 from 67.

Mr Vevers explains that, aside from efficiency benefits, this reduction in footprint enables Hyde to become more of an influential landlord in the local authority areas it operates within, and to be part of the conversation around joint venture opportunities.

“We can be at the table influencing [so] we can support any agenda for change that they have, particularly through the use of social housing,” he says. “For example, if they have too few social housing units for younger people or older people, then we can talk to them and say: ‘Well, actually if there’s any need from the quantum of assets that we’ve got, we can be helpful.’”

Elsewhere, housing associations are increasingly turning to stock rationalisation as a means to grow or reduce their holdings of certain stock in order to become more specialist or to exit tough markets.

As Savills’ Ms Collins explains: “Quite a lot of housing associations have withdrawn from supported housing because of difficulties in the market, [in contrast to] specialists like Advance Housing and Support, Housing & Care 21 and Anchor on the older person’s side, or Home Group, which have got a

big supported housing outfit.”

Those remaining in the market are operating at scale in order to insulate against risk, she says, with specialists looking to aggregate and build their portfolios.

For-profits

The recent growth of for-profits entering the social housing sector has created some nervousness around exactly how housing associations engage with them in the stock rationalisation market, especially when it comes down to tenant consultation and regulatory risk.

For the year to March 2018, the official figures record 37 for-profit registered providers, which is up from just 18 five years earlier.

Ms Collins says that it is important for the social housing sector to “dig into the detail” about exactly who has registered and what their business does.

For those profit-making registered providers that have entered the market, an increasing amount are looking to stock rationalisation, says Charles Cleal, director of residential at JLL.

“They are becoming more and more active and we’re seeing a lot of them bidding for stock. They tend to bid for full portfolios, where you might otherwise be dealing with two or three bidders.”

The reason for this, Mr Cleal says, is because for-profits are less worried about geography compared with some housing associations which might typically bid for certain lots within a portfolio.

“Those [for-profits] who are bidding properly have RP management partners lined up ready to take the stock on and manage it. So, they present their bid as a partnership of them funding it and an RP managing it, and those tend to be quite long arrangements.”

For organisations like Hyde, however, working with for-profits is not on the immediate agenda. Mr Vevers believes there are no benefits to trading with for-profits and says Hyde “hasn’t been close to any sales”.

This is largely down to price, he says. “Generally, they’re not interested in what we’re selling. What they’re interested in buying is Section 106 units that are brand new, from house builders or otherwise.”

In terms of how or whether that may change in the near future, Mr Vevers believes that it will take around two to five years before larger for-profit organisations start to alter their business plans.

Elsewhere, Mr Vevers adds that many of the new entrants in the market are also eyeing shared ownership portfolios. “I can see that might be quite an interesting one, because it’s a very different product but it is something that [for] a housing association, it’s a staple for us. But there are others, because it doesn’t have the same level of management requirement.”

Tenant satisfaction and engagement, brought to the fore after the Grenfell Tower tragedy, will also be a significant factor in the stock rationalisation market for both new and existing players.

Organisations such as Guinness and Hyde already involve customers in the transfer process, but Mr Cleal adds that this is now becoming more common among housing associations, whereby a tenant member would be included on the selection panel.

“The tenant here would be inspecting [the plan] mainly from a qualitative perspective rather than financial, so they’d be asking: ‘Will they be getting a good landlord?’,” he says.

Deregulation

One party ostensibly less involved in the transfer process today is the regulator. Following the deregulation of disposal consents, housing associations are now required only to notify, rather than seek approval in advance.

As yet, this has not led to a flurry of stock leaving the sector. The recent Statistical Data Return (SDR) shows that the total amount of social rented and low-cost home ownership (LCHO) stock lost from large providers in 2018 decreased by 3.3 per cent to 22,966 units, down from 23,732 in 2017 (a decrease “driven by a reduction in the number of LCHO losses”, the SDR notes). Meanwhile losses of social rented stock for large providers grew slightly to 18,263, up from 17,350 in 2017 – but down from 18,419 in 2016. As the report notes: “There is no clear evidence that the deregulation of disposal consents has yet led to any material change in the level of losses.”

For Robert Grundy, head of housing at Savills, the impact of deregulation is “minimal in terms of RP behaviour”, although it does place the onus on the registered provider and the board “to make sensible divestment decisions, with potentially severe consequences if they get it wrong”.

He adds: “What we haven’t yet seen is trading of tenanted stock to a non-registered entity which is theoretically possible... The reason for this being that the consequences could be quite severe; it could be more than just a regulatory downgrade.”

Where housing associations are concerned, Mr Cleal at JLL notes that some have recognised the potential to create financial value. “Some of our clients are considering deregulation as an opportunity to sell some assets outside of the sector where appropriate, such as where the financial receipt of the sale of a high-value non-performing asset can provide more affordable homes elsewhere.

“However, the sector very much retains its social purpose and assets being sold outside the sector at present remain a very small percentage of total social housing assets.”

This raises the question of the mooted market value – social housing (MV-SH) pricing measure, which would sit alongside, rather than replace, the current existing use value – social housing (EUV-SH) and market value subject to tenancies (MV-T). MV-SH would recognise the potential for properties traded between providers to be sold out of the sector when they become void, and has been estimated to offer up to a 15 per cent uplift in valuation.

Mr Grundy, one of the designers of MV-T along with JLL, feels that people in the sector “are reasonably content with what we are putting forward”, but does not anticipate a huge rush towards using it. Progress is pegged, too, on agreeing the proposal with the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Where the lender viewpoint on MH-SH is concerned, Mr Grundy emphasises that the main consideration is the current commercial relationship with the borrower; the loan agreements and amount of debt already in place. “Quite a few lenders don’t appear to have that much appetite to lend more at the moment and so I think a lot of it has to do with their appetite for new business,” he says. However, he sees potential for new lenders not tied by the terms of existing debt to have more appetite for using MV-SH.

He also notes that under MV-SH, values may be “slightly more volatile than under EUV-SH, which historically hasn’t had big swings”.

Lenders

On the issue of stock rationalisation more broadly, there’s a general consensus that the banks are supportive of the market – as long as they are involved in the process.

Ms Collins notes: “Where you’ve got organisations that are selling stock that might be currently used as security for loan purposes, they will need to involve lenders and provide replacement stock.”

For Stuart Heslop, managing director of real estate finance for Scotland and North England at Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), stock rationalisation makes “perfect sense”.

“It seems to be an active part of what the associations have been doing over the years and I don’t see that slowing down,” he says.

While he doesn’t take a view on MV-SH, as a lender with a background outside of social housing until recently, he makes an interesting wider point around valuation: having a “really consistent pattern” of assets trading in a commercial marketplace provides a price point for assets used as security against loans.

“You didn’t really have that before with social housing,” Mr Heslop says. “So what stock rationalisation has done is given a price point because we’ve seen assets trade. It’s given lenders a bit of confidence that the valuations we hold have actually got some validation of that valuation methodology because we’ve seen some trades in the market that aren’t distressed trades – they are absolute assets moving between different parties at a price.”

As the market matures then, this confidence could give housing associations the tools they need to grow their organisations efficiently.

As Mr Heslop puts it: “If you’ve got a more efficient business, you’ve got a more robust future cash flow and it makes it a much easier lending proposal with cash flow to service additional debt that can then go into building future stock.”

RELATED