Lease-based supported housing model in question

With several lease-based RPs found non-compliant, Sarah Williams takes a closer look at the model

The head of a specialised supported housing (SSH) provider forced to renegotiate its leases with creditors last year has revealed that it would look to take on new business if it can ensure a “sensible, sustainable way forward”.

First Priority, the first of several lease-based providers to be found non-compliant by the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH), fell into severe financial difficulty and reached a company voluntary agreement last July. Some of its previous landlords moved its leases to other registered providers (RPs).

John Higgins, who stepped in as First Priority’s chief executive in autumn 2017, said that creating sustainable parameters for new business would be challenging, but added: “we believe it’s doable”. As part of this, the board has modelled its weekly margins over a 25-year period to assess sustainability.

First Priority recorded a loss of £5.8m in its accounts for the year ended 28 February 2018, citing “high bad debt provision, the majority of which relates to void income invoiced to care operators, as well as a shortfall of service charge income against service charge costs”.

The accounts also noted that the provider was considering a “debt for equity swap” with its main funder Topland Henley Healthcare Investments.

However, Mr Higgins told Social Housing that it has not further pursued the proposal. “We want to maintain not-for-profit status, and [that] represented a big challenge for us on debt for equity.”

Instead the provider has focused on implementing the recommendations of a review of its governance arrangements conducted last August, including refreshing its board.

Lease-based model

Mr Higgins’ views come after the RSH further scrutinised the lease-based model in a lengthy addendum to its Sector Risk Profile, in April.

Lease-Based Providers of Specialised Supported Housing highlights five key themes, including poor risk management and inappropriate governance practices by some RPs and “a lack of assurance as to whether appropriate rents are being charged”. It also flags the “thin capitalisation” of some providers and the “concentration of risk” in having tight margins and exposure to inflation through long-term Consumer Price Index-linked leases.

Five other providers – Trinity, Westmoreland, Inclusion, Encircle, and yesterday Bespoke Supportive Tenancies – have been found non-compliant for governance and viability.

Another, Sustain UK, was rated G3/V2. It does not take out the typical 20-year-plus leases described in the RSH’s addendum but undertakes shorter, three-year leases.

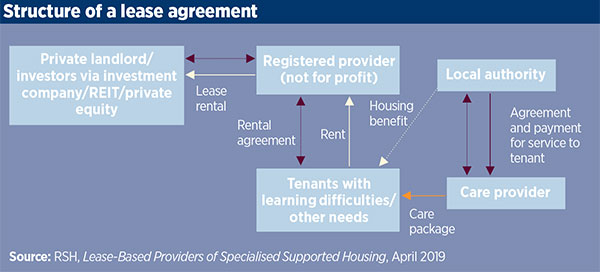

In commissioning SSH, some of the payment burden is removed from local authorities, because while the support delivered by a care provider is funded through the authority’s social care budget, the cost of the accommodation shifts to central government, through housing benefit.

Provided that SSH meets the relevant rent regulation, councils can treat claims made by tenants as ‘exempt accommodation’ entitled to enhanced housing benefit above the capped levels imposed on general needs social housing. But providers are normally required to be non-profit.

In an April 2019 regulatory judgement, the RSH described Encircle’s current “for-profit” registration status as presenting an “additional risk”, and in March the RP converted to a community benefit society.

Accommodation eligible for housing benefit also cannot have received any public subsidy in its development. The RSH report acknowledges that private finance “plays an important role”, but it questions the sustainability of provision where RPs do not sufficiently manage risks.

In an interview with Social Housing, Paul Bridge, chief executive of Civitas Housing Advisors, said that because there is no recourse to public subsidy, these RPs “won’t have large amounts of capital”. But he added: “If they’re well run… they will generate a return from the overall rent because there is a service charge they are allowed to claim from the local authority.”

This return can be typically “up to 20 per cent”, he said.

However, Mr Higgins said: “The way the leases are structured originally… doesn’t leave a huge amount of space for the RPs to actually have a margin.”

While some risks can be contracted out via insurance or nomination agreements (whereby the care provider or council covers voids for a set period), this still leaves gaps.

RPs are also reliant on local authority commissioning practices. Mr Higgins cites one borough where a “very robust on-boarding process” can mean it is three months before a nomination is made.

Investment value

Leases that RPs take out with private investors are normally “fully repairing and insuring”, with no break clauses, meaning that the RP covers the full cost of maintenance and is liable to pay its leases in the instance of voids.

The RSH also emphasised that business models that assume income will be covered by housing benefit are “exposed to future changes in welfare”. Making this assumption also means that the value of the property on the open market – should it be sold to recoup costs for a financially struggling RP – is far lower than the investment value on which its leases (and often the investor’s original purchase) were priced.

One real estate advisor told Social Housing that they had seen deals where an SSH property’s market value was “worth less than 30 per cent of its investment value – yet someone is giving 100 per cent of investment value as a purchase price”.

Mr Higgins said: “It’s essentially 100 per cent interest cover on 100 per cent occupancy – which, if you phrase it quite like that, most organisations wouldn’t go near.”

But he added that small organisations with limited access to capital look at the financing model “for the right reasons” as a means to increase provision for vulnerable adults.

RELATED