Power-sharing and social housing in Northern Ireland

A healthy power-sharing system in Stormont is crucial for the social housing sector to function well. James Twomey reports

On a violent day in October 1968, a riot broke out on the streets of Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland, as protesters challenged what they saw as the provision of housing in the area along sectarian lines. This theme would become a driving force for the period of violence that then followed, given the understated name of ‘The Troubles’.

At the time in the city, the allocation of housing was largely being decided by a unionist and Protestant-dominated local authority that was seen to be discriminating against the Catholic and nationalist population.

In 1969, the Cameron Commission was established to investigate this period of escalating violence in the region and found that “pressure was building up among the Catholic section of the population” as housing supply failed to meet demand. This sense was heightened by the fact that the voting system favoured ‘ratepayers’ – including homeowners and council house tenants – which created an effect of disenfranchising Catholics and republicans.

More than 50 years later, the era of violence has dimmed but the root problems can still be seen today in Northern Ireland – and, where social housing is concerned, they still resonate.

According to the Northern Ireland Federation of Housing Associations (NIFHA), 90 per cent of social housing estates are still single-identity, although a 2017 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey found that 78 per cent of people would prefer to live in a mixed-religion neighbourhood.

Add into the mix new problems for the region – Brexit and a botched Renewable Heat Incentive scheme, which saw the Northern Ireland Executive effectively paying businesses’ energy bills – and the power-sharing arrangement has broken down for the second time in five years.

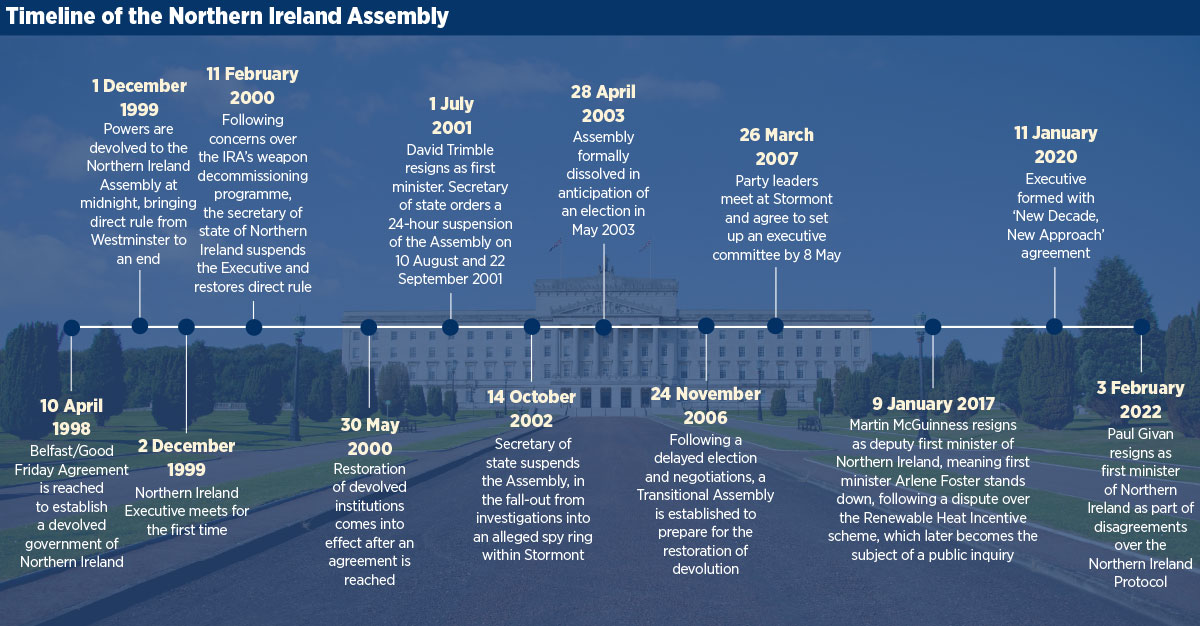

The power-sharing arrangement means that the top two seats in Stormont – first minister and deputy first minster – must be shared by a nationalist and a unionist representative. Under the rules of the Good Friday agreement – established in 1998 – when one steps down, so must the other, creating a dissolution of the assembly until a new power-sharing arrangement can be agreed.

On 3 February 2022, the first minister of Northern Ireland and Democratic Unionist Party member Paul Givan announced that he would be stepping down over disagreements around the Northern Ireland Protocol – designed to prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and EU member Republic of Ireland after Brexit.

This breakdown in government clearly has a stultifying effect on political progression in the country, but the impact can be felt through all walks of life in Northern Ireland, including the social housing sector.

The draft budget

Provision of social housing is shared between the Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) – which performs a similar function to councils in England and Wales, and manages around 85,000 homes – and 20 housing associations that provide around 53,000 homes.

The grant funding for the NIHE’s development and management of its stock comes from the Executive’s budget, which in a time of breakdown could affect the allocation of those funds.

In December 2021, the draft budget for 2022-25 was published. It drew concerns over funds for housebuilding across the country as it proposed a two per cent re-route of other departments’ finances towards the health department’s budget.

But the draft budget may remain just that, as the finance minister announced that there can be no approval without a fully functioning Executive. The last suspension of the Executive lasted three years.

Grainia Long, chief executive of the NIHE, tells Social Housing: “Given the withdrawal of the draft budget, it is now unclear what this means for the Housing Executive and the housing sector in terms of funding availability. It is assumed, initially, that this will mean departmental budgets will largely mirror funding availability of recent years.”

Ms Long is keen to point out the effect this could have on temporary accommodation in the region, where an estimated 6,100 people will be living in 4,250 units of temporary accommodation by the end of the current financial year. In addition, the roll-out of draft government strategies such as the Housing Supply Strategy, the Environmental Strategy and the Intermediate Rent Policy may also be affected.

Carol McTaggart, chief executive of Clanmil, one of Northern Ireland’s largest housing associations, says the context for this draft budget is “one of challenge”.

She says: “The Brexit Protocol, COVID-19, climate change, fire safety – there are so many important issues that need to be addressed by the Northern Ireland Assembly. We need a working Executive. Without the certainty this provides, the housing sector will be hampered in meeting the needs of its customers and the communities we serve.

“Without a three-year budget approved by the Executive, uncertainty around funding could also have a major impact on our charity sector partners, who provide services that our customers rely on.”

Housing associations in Northern Ireland receive about 50 per cent of funding for new build social housing through the Housing Association Grant (HAG), according to NIFHA. This is typically matched by private finance, which housing associations can secure, and enables them to deliver twice as many homes.

According to Ms McTaggart, political uncertainty may impact lenders’ views of the housing association sector in Northern Ireland. “Given the continuing housing crisis in Northern Ireland, we must be able to give our lenders certainty in order to ensure continued access to this essential funding,” she says.

The last time there was not a functioning Assembly and Executive, the UK government took very limited decisions on a wide range of day-to-day issues, which made it difficult to deliver progress on housing issues, according to Ben Collins, chief executive of NIFHA.

When there are increasing costs for new build housing or services, in the absence of the Executive being able to allocate additional funds, this creates further pressure for housing associations.

Mr Collins says: “We do have concerns about the funding which is available for new build housing. At a time when the numbers in housing stress continue to increase, there is an urgent need to increase the overall numbers of social and affordable housing.

“The housing association sector in Northern Ireland is facing a number of challenges, providing homes and services for tenants during a pandemic, dealing with rising materials and construction costs, [and] complications arising from Brexit.

“The resignation of the first and deputy first ministers creates some additional issues which we have to address. It creates uncertainty and does affect the ability to secure additional funding beyond that which is already committed, as can be seen by the inability to approve the draft budget. However it is a resilient sector, one which is determined to continue to provide much-needed social and affordable homes.”

On the point of whether NIFHA would support for-profit providers entering the Northern Irish market, Mr Collins says: “No, we believe that there is merit in the current situation where housing associations in Northern Ireland

are also registered charities and have a commitment to reinvesting any surpluses back into their social purpose.”

Housing stress

Like all nations in the UK, the need for increased supply of social homes is acute in Northern Ireland. As of 31 March 2021, there were 43,971 applicants on the social housing waiting list. Of these applicants, 30,288 were in “housing stress”, meaning they were unlikely to be in safe or suitable accommodation. In 2020-21, 9,889 households were accepted as statutorily homeless.

The Social Housing Development Programme (SHDP), which is managed by the NIHE, provides grant funding to housing associations so that they can build or acquire new social housing, including through the HAG.

Since 2010-11, 16,313 social homes have been completed through this programme and in 2020-21, there were 1,304 completions – a 20 per cent decrease on 2019-20, when there were 1,626.

In the last three-year cycle, from 2018-21, the budget for the SHDP totalled £403.7m. The current SHDP budget for 2021-22 is £178m, while the budgets for 2022-23 and 2024-25 have yet to be confirmed.

Ms McTaggart says: “We understand from the NIHE, who manage the sector-wide SHDP, that the target for 2022-23 is 1,900 new social homes. Given the current waiting lists for social housing, we had anticipated that the number of new homes for each of the next three years would have been circa 2,200 per annum.

“However, the proposed capital funding for new social homes in the draft budget could mean that the number of new homes delivered could fall by year three to around 600 to 800 homes. This is really worrying for people who live in unsuitable housing conditions or have no home to call their own. With waiting lists for social housing at their highest for 10 years, this simply cannot be allowed to happen.”

“With waiting lists for social housing at their highest for 10 years, this simply cannot be allowed to happen.”

Carol McTaggart, chief executive, Clanmil

Elsewhere, at a time of heightened living costs, a supply chain crisis and concerns over fuel welfare, the absence of a government can have real impact on those who need it most to function.

Legislation approved before any suspension of the Assembly is typically able to pass during an absent government. But although the departmental ministers can remain in their posts, they are limited in what they can do.

Four days after the most recent dissolution of the Executive, legislation was passed that will help hundreds of families, some of which are likely to be in social housing, access ‘mitigation payments’ that will be available to more people who currently have their benefits reduced because of the ‘bedroom tax’ and a benefit cap.

But there are concerns that a missing Executive could mean delays in implementing this.

Roderick Canning, director of finance at Apex Housing Association, which recently sealed a £100m investment from the Pension Insurance Corporation, tells Social Housing: “The Northern Ireland Assembly’s work to further extend welfare reform mitigations until 2025 is to be welcomed. This financial support helps thousands of households maintain their tenancy and protects them from the effects of the bedroom tax and benefit cap.

“Social housing grants are essential for the provision of social housing in Northern Ireland. With rising building material costs, increased requirements to meet future net zero targets, and a continuing increase in demand, it’s important that grant levels continue to reflect the cost of provision.

“Like anywhere in the UK, social housing providers in Northern Ireland need a strong, stable and secure government. The lack of a functioning NI Executive does not stop our day-to-day work – however, it could impact on our capacity to plan effectively into the future.

“Any absence of political leadership may also lead to the potential stalling of important new strategies to enhance housing provision in the province.”

Private finance

John McLean, chief executive of Radius, Northern Ireland’s largest housing association, says that, in the short term, a breakdown of the Executive was “extremely disappointing” for the people of Northern Ireland but could be managed within the sector provided it did not drag on for too long.

Mr McLean was keen to highlight the investment prospects for the sector should a swift resolution to the government’s impasse be found.

“If it continued in the long term, it could start to affect pricing and the availability of the numbers of people who might be prepared to invest,” Mr McLean says.

“The flipside of that was when we went out to London, and we went to the US for our placement around two-and-a-half years ago [when the Executive resumed after a nearly three-year suspension], we had a very positive response from the investors on the back of the good news stories coming in.

“If we get our act together here, the [Northern Ireland] protocol sorts itself out, the parties get restarted again, actually, that could be quite a positive note on which to go looking for finance.”

Upcoming elections

Looking forward, in May 2022 Northern Ireland’s residents will return to the voting booths to elect its newest Assembly, with 90 seats available.

However, there is concern growing that the same issues over the Northern Ireland Protocol will prevail and prevent an Executive returning to business.

With an ever-growing waiting list for social housing, environmental objectives from central government, fire safety concerns and spikes in violence reminiscent of darker days, the tenants of social housing in Northern Ireland need a functioning Assembly sooner rather than later.

RELATED