Right to reply: what the sector really thinks of the RTB extension

A plan to extend the Right to Buy has resurfaced. James Wilmore speaks to stakeholders across the sector about what it means for housing associations

“If this policy does go ahead, it’s going to put the cat amongst the pigeons,” says Richard Petty, head of JLL UK’s Living Advisory. “I haven’t spoken to anybody in the sector who welcomes it.”

After a seven-year build-up, the Conservative government is promising again to give housing association residents the right to buy their home. In a speech just days after surviving a bruising confidence vote in his leadership, Boris Johnson last month (June) announced much-trailed plans to extend the Right to Buy. “Now is the moment to widen the possibilities, and to give greater freedoms to those who yearn to buy,” he told an audience gathered in Blackpool.

Mr Johnson suggested that the 2.5 million households who live in housing association-owned properties are “trapped”.

“If this policy does go ahead, it’s going to put the cat amongst the pigeons”

He said: “They cannot buy, they don’t have the security of ownership, they cannot treat their home as their own or make the improvements they want. And while some housing associations are excellent, others have been known to treat their tenants with scandalous indifference.”

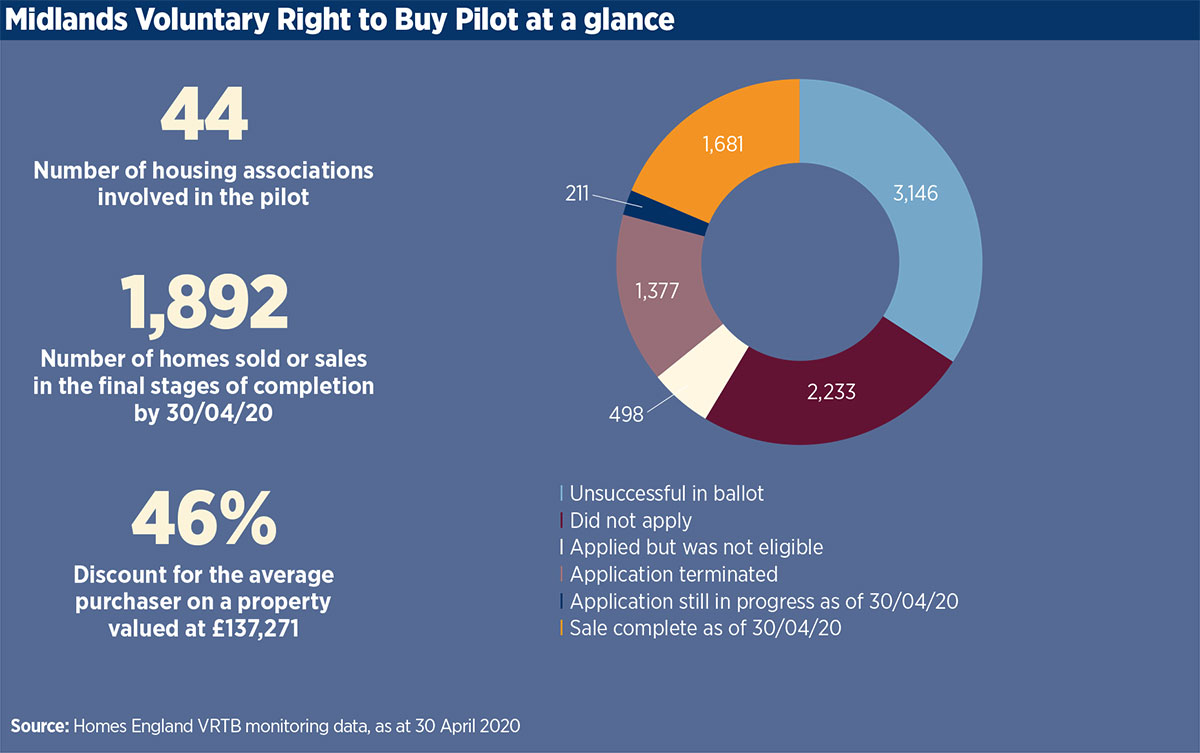

The idea of extending the controversial scheme, introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the early 1980s to allow council tenants to buy their homes, was announced by David Cameron in his 2015 election manifesto. He vowed to introduce a scheme in his first 100 days in office, but it never materialised. Instead, his successor Theresa May introduced a pilot scheme in the Midlands in 2018.

However, a year after its launch, it was revealed that only £10m out of a pot of £200m had been spent on the scheme following low take-up. Now the government has decided it is time for a wider roll-out.

The housing sector has long had concerns about the proposal. And with the prospect of it becoming a reality moving a step closer, these fears have escalated. Among the more eye-catching reactions, Shelter’s chief executive Polly Neate branded the plan “a dangerous gimmick”.

So what could be the impact on the sector if the policy does go ahead? For Mr Petty, one of the main issues for housing associations will be whether they will receive all the proceeds from a sale, or whether some will go to the Treasury.

Mr Johnson also promised that there will be a “one-for-one replacement” for each housing association home sold. But Mr Petty says: “The issue is whether you will get enough receipts to pay for the replacement of the home.”

A further worry is “the adverse impact” on the sector’s borrowing capacity, Mr Petty says. “Given that fundamentally the sector borrows against the value of its rental income, as you lose assets, you are losing the ability to borrow,” he says.

“Given that most of the sector is trying to borrow on MV-T, I think there will be a reduction in MV-T values unless funders have a get-out-of-jail card. You’re eroding the borrowing capacity of the sector and you’re going to struggle to replace those homes.”

Abigail Davies, a director at Savills Housing Consultancy, also highlights the financial stress it could create for housing associations. “If you’ve got an active and unpredictable disposal programme due to the Right to Buy, you then need to have enough headroom in your security pool to manage that.”

Questions have also been raised over what types of homes will be built back. “I think we’ve seen some real tensions around rented stock being sold and a tendency for that to be shared ownership when it comes back,” says Ms Davies. “People are quite acutely aware of the desire to provide rented homes at the moment. So there will be a requirement [for landlords] to have a good think about what that development process looks like and how receipts get re-reinvested.”

Another big question mark that hangs over the policy is whether it will be voluntary or mandatory, and how it will be funded. Under questioning from MPs on the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Select Committee last month, housing secretary Michael Gove hinted that it may not be compulsory, saying that housing associations will be “seduced” to join. As to whether housing associations would sign up, Mr Gove said: “My intelligence so far is that while housing associations quite rightly have a number of questions, they are not opposed in principle – quite the opposite.”

“Announcements like this pique a lot of interest, and then people find that maybe it’s not quite what they thought”

Either way, Mr Johnson said the government would “work with the sector” to introduce the scheme.

Mr Petty says: “I think it might be voluntary, that might be what’s in the government’s mind.” However, he identifies a key problem with this: “If you’ve said to housing association tenants you will get the right to buy your own home and then you make it voluntary and your landlord opts out, you’ll have a lot of really disgruntled housing association tenants saying, ‘Boris, you promised me that I could buy my home and now you’re telling me that I can’t.’”

Ms Davies reiterates this point, saying that the government has raised expectations that might not be “terribly well aligned with how it will actually pan out”. She adds: “Announcements like this pique a lot of interest, and then people find that maybe it’s not quite what they thought.”

On the issue of funding the extension, Mr Gove did not inspire confidence when pushed during the select committee hearing. “I am not in a position yet to say exactly how it will be funded,” he said.

John Perry, a policy advisor at the Chartered Institute of Housing, says there could be a “huge amount” to compensate housing associations for, in discounts. During the pilot, discounts were averaging about £65,000, he says. “It seems unlikely that there’s going to be sufficient money to have a really big nationwide scheme.”

But he says if the money is limited, and it is a small scheme, then associations “might feel that it’s better to co-operate than to appear to not co-operate”. Mr Perry also suggests that a small voluntary scheme is unlikely to be an issue for housing associations’ borrowing capabilities. But he adds: “If it was a big scheme or compulsory in any way, I think that could be problematic.”

It will be interesting to see how take-up varies across country. Mr Petty does not believe it will be significant in London because of the price of property. “The greatest impact is probably going to be on non-transfer landlords in the shires with a mix of suburban and rural stock,” he says. “This is because you’re more likely to be able to exercise the right to buy in Buckinghamshire, Hampshire or Kent than you are in Islington.”

He adds: “The shire associations could see a sudden loss of family homes and they are the ones they most need. And it will be harder for G15 landlords to replace lost units, because the more urban you are, the more difficult it is to acquire sites and build.”

Assuming the policy does go ahead, what can be learned from the Midlands pilot? Stonewater, which manages homes across England, was among the housing associations that participated in the scheme. Sue Shirt, executive director of customer experience at the association, says the pilot demonstrated that there was a “massive appetite” among tenants to buy their home.

“Our experience was there was definitely a demand,” she says.

“I don’t think we should be surprised by that because as a society we encourage people to go into homeownership.”

“The fundamental flaw here is we’ve got a housing crisis and this policy is not going to increase supply”

However, Ms Shirt has reservations about the scheme being introduced now. “I don’t think the timing is right, if I’m honest,” she says. “One-for-one replacement is more difficult now because of cost price inflation, land inflation, availability of labour and the timeline between the sale and the replacement. We know the time lag is two years even if you have something in the pipeline. One-for-one replacement is possible in some parts of the country, but will be more difficult in more expensive parts of the country.”

But she adds: “The fundamental flaw here is we’ve got a housing crisis and this policy is not going to increase supply.”

Large Midlands association Platform was also part of the pilot scheme. Rosemary Farrar, the 46,000-home landlord’s chief financial officer, says the social housing lost through the pilot has “not proved easy to replace”.

However, if it does get a wider roll-out, Ms Farrar believes it will not lead to a large number of homes being sold. “As a result, we have not done individual stress-testing on this risk but have rolled it into the detailed review of our development appraisal assumptions,” she says. But she adds: “It will inevitably have some negative impact on the capacity for building new homes and for improving the homes of our existing customers, which we will endeavour to minimise.”

Of course, the elephant in the room is the question of whether this policy will come to fruition this time. As Social Housing went to press for its July print edition yesterday (5 July), Mr Johnson was still prime minister but struggling to deal with discontent from his party over a variety of controversies.

As Ms Davies says: “I haven’t picked up a huge sense of concern [in the sector]. I don’t think people are necessarily expecting it to be their biggest policy priority in the coming months.”

And Mr Petty concludes: “I sincerely hope [the Right to Buy extension] won’t happen. I don’t think it will be fundable, that’s the thing that will stop it. If I had to put money down on it now, I would say it won’t see the light of day, either because we’ll have a change of prime minister or a change of government.”

Sign up for Social Housing’s weekly news bulletin

Social Housing’s weekly news bulletin delivers the latest news and insight across finance and funding, regulation and governance, policy and strategy, straight to your inbox. Meanwhile, news alerts bring you the biggest stories as they land.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

RELATED