Special report: four key themes in the Housing Revenue Account

Steve Partridge of Savills explores which important factors have moved over the period that our Housing Revenue Account analyses cover

In March, we published our annual national analysis of the Housing Revenue Account (HRAs) for the financial year 2020-21.

This was the fourth full year of our analysis covering the five financial years from 2016 to 2021 and, as usual, we highlighted the key and significant trends in HRA income, expenditure, debt and investment capacity as the sector continues to develop its plans post-debt cap and, now, post-pandemic.

In summary, we highlighted that with 2020-21 being the first financial year of a return to rent increases following four years of rent cuts from 2016 to 2020, we saw a net increase in debt and asset values, suggesting that authorities are beginning to bring forward more investment over time, and at the same time saw a consolidation of capacity for future investment as rents and turnover increased and operating costs were

held under control.

All key measures and metrics we use to describe the capacity for the sector to invest – and by extension, the capacity of the sector to withstand challenges from inflation, extra spending pressures etc – either stabilised or strengthened during 2020-21.

Behind the headlines are some diverging experiences locally, and in this article we have aimed to draw out some of the key differentials in a little more detail. First a little bit more detail in relation to the trends over the five-year period to 2021, second in the experiences between different types of authorities and in different regions, and third in how some authorities may be differentially impacted around the average experiences for the sector.

We noted back in March that as a result of pandemic-induced delays, some authorities were affected by local government reorganisation and many were affected by what appears to be a general and ongoing shortage of audit capacity within the sector as a whole.

There were 12 authorities that had yet to finalise their accounts for 2020-21, and so we confined the majority of our trend analysis to those authorities for which we have complete information for all years. There are a number (five) that have since published their accounts and we have worked this into the analyses below as appropriate.

In our first article in March, we set out how the main capacity metrics had moved during the period to 2021 relative to a starting point of 2017-18. Which other key factors have moved over the period that our analyses cover? And what might they show? We have picked out four statistics to highlight some key themes.

Average rents

While we do not have detailed data published for 2016-17, the chart shows the four years from 2017 to 2021, and how rents reduced in the final two years of the rent cut period and then recovered in 2020-21.

The percentage changes are not exactly the one per cent reductions and Consumer Price Index (CPI) plus one per cent increase expected – there are plenty of factors influencing average rents, including re-lets at higher (target) rents, the impact of affordable rent conversions for grant-funded new build programmes, and new build social rented homes being generally at a higher rent than the existing stock. Nevertheless, the chart paints a picture of the challenges faced by local authorities during the rent cut period and how increases can be and have been a stimulus for investment.

Gross asset values

We again highlight below the challenges around asset valuation methodologies, but as the chart shows, the principal driver towards increased value (ie open market values) showed a significant increase through the five-year period from 2016 to 2021, increasing just less than 10 per cent overall despite stock loss through the Right to Buy amounting to 1.7 per cent over the period.

While the underlying strength of HRA assets in market value terms is not in doubt, local authorities are never able to realise this value – either through having to sell properties under the Right to Buy at large discounts or otherwise maintaining tenancies in perpetuity. And debt is not secured on asset value for local authorities as it is for housing associations.

Operating margins

Trends in operating margins are also an interesting area to focus on, as these margins provide the capacity through which to invest in borrowing and to cover debt financing costs.

In the first two years of the rent cuts, average margins showed significant resilience despite real drops in income. In the final two years of the rent cut period, as might be expected, margins declined as authorities sought to maintain services in the face of income reductions.

The positive outcome in 2020-21 – which we might expect to see carried forward to 2021-22 when the accounts are published – is that margins recovered as rents were allowed to increase again.

Debt/unit

There was a reduction in unit debt in the second year of the rent cuts as authorities continued to face the debt cap and at the same time needed to take defensive action against reducing income. The 2017 period was also one where the additional threats of the sale of high-value voids, and Pay to Stay, affected investment confidence.

Since 2017, however, the clear trend is for an increase in borrowing as confidence has been boosted by the abolition of the debt cap, a focus on new supply and investment, and a return to rent increases.

We tend to highlight that average debt levels in the HRA sector are well below the housing association equivalent, which in some cases for investing associations can be as high as £30,000 per unit or more. Only 12 authorities have unit debt above this level, highlighting the relatively low gearing within the HRA sector.

Operating costs vary around a national average of £1,800 per unit for total management, £1,146 per unit for maintenance and £1,063 per unit for major repairs, a total of £4,009 per unit for all costs.

This was an increase of less than one per cent on the totals for 2019-20. We wanted to test this a little further in terms of whether particular groups, types or sizes of authorities tended to suggest higher or lower costs.

Regional differentials

As would be expected, we see London as a clear outlier on management costs, reflecting both the additional core costs of managing stock in the city, and the much higher number of flats as a proportion of the stock than the national average.

Turnover is also much higher per unit in London as a result of higher service charges levied to flat tenants and leaseholders.

All other regional averages are below the national average. Excluding London, average management costs would be £1,336 per unit. The three Southern and Eastern regions are therefore above this non-London average, while the five Northern and Midlands regions are below this average. The lowest unit management costs were found in the West Midlands.

For maintenance costs, London boroughs are, by contrast, much less of an outlier, with an average of £1,394 per unit. The lowest maintenance costs were found in the South West and Yorkshire and the Humber, but with a remarkable degree of consistency across unit repairs costs regionally.

It is interesting to note that the lowest management costs were in the West Midlands, which also saw the highest maintenance costs outside London.

Operating costs by region

| Region | Number of units | Unit costs 2020-21 (£) | |||

| Average management | Average maintenance | Depreciation/top-ups (average) | Total | ||

| London | 373,693 | 3,190 | 1,394 | 1,344 | 5,928 |

| East of England | 155,203 | 1,483 | 1,062 | 1,229 | 3,774 |

| South East | 144,413 | 1,787 | 1,056 | 1,176 | 4,019 |

| South West | 88,073 | 1,470 | 996 | 1,068 | 3,535 |

| East Midlands | 157,034 | 1,207 | 1,083 | 805 | 3,096 |

| West Midlands | 187,195 | 1,129 | 1,190 | 896 | 3,215 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 233,180 | 1,198 | 997 | 777 | 2,973 |

| North West | 72,540 | 1,313 | 1,027 | 1,035 | 3,376 |

| North East | 80,001 | 1,242 | 1,036 | 971 | 3,248 |

| England totals | 1,491,332 | 1,800 | 1,146 | 1,063 | 4,009 |

Transfers to the major repairs reserve were again higher in London, reflecting the higher costs of long-term capital repairs, but also presumably higher values driving the depreciation calculation.

The transfers in some regions were well below £1,000 per unit on average, which is interesting given that the standard long-term maintenance profile derived from stock surveys tends to be in the region of at least £30,000 per unit over 30 years, ie £1,000 per year.

Type of authority

The table below highlights differential costs by the type of authority, split between district councils, London boroughs, metropolitan councils and unitary authorities.

Perhaps one of the most striking outputs within this table is that average management costs in metropolitan boroughs are the lowest of any authority type. This might reflect the fact that these authorities are in the North and the Midlands, however it might also be seen as unexpected given the density, complexity and urban nature of the stock in these authorities.

In addition, the amounts transferred to the major repairs reserve within the metropolitan boroughs are also well below the national average, suggesting either that the stock in these boroughs has lower longer-term needs than other authorities (which seems unlikely) or that lower values are driving lower depreciation charges.

Either way, it will be interesting to see how this evolves over the next few years given greater investment pressures on existing stock from building safety and other regulatory legislation.

Operating costs by authority type

| Type of authority | Number of units | Unit costs 2020-21 (£) | |||

| Average management | Average maintenance | Depreciation/top-ups (average) | Total | ||

| District | 373,288 | 1,368 | 1,018 | 1,038 | 3,425 |

| London borough | 373,693 | 3,190 | 1,394 | 1,344 | 5,928 |

| Metropolitan | 395,733 | 1,191 | 1,081 | 867 | 3,140 |

| Unitary | 348,618 | 1,464 | 1,090 | 1,010 | 3,564 |

| Totals | 1,491,332 | 1,800 | 1,146 | 1,063 | 4,009 |

Size of authority

We have grouped authorities into ‘large’ for those with more than 15,000 tenanted units at 31 March 2021, ‘medium’ for those between 6,000 and 15,000 tenanted units, and ‘small’ for those with fewer than 6,000 tenanted units.

The table below shows that there are few statistically significant outputs that cannot be explained through the regional or authority-type analysis.

The higher average maintenance costs for larger authorities are likely to be primarily influenced by larger London boroughs, although the medium-sized London boroughs also appear to be driving higher management costs within this group.

We will reflect further on this element of the analysis to see whether we can derive any sense of ‘size matters’ when considering average costs of delivery.

Operating costs by authority size

| Type of authority | Number of units | Unit costs 2020-21 (£) | |||

| Average management | Average maintenance | Depreciation/top-ups (average) | Total | ||

| Large (more than 15,000 units) | 732,092 | 1,768 | 1,228 | 1,006 | 4,003 |

| Medium (6,000-15,000 units) | 475,392 | 2,040 | 1,086 | 1,180 | 4,306 |

| Small (fewer than 6,000 units) | 283,848 | 1,480 | 1,033 | 1,013 | 3,526 |

| Totals | 1,491,332 | 1,800 | 1,146 | 1,063 | 4,009 |

Distribution of capacity

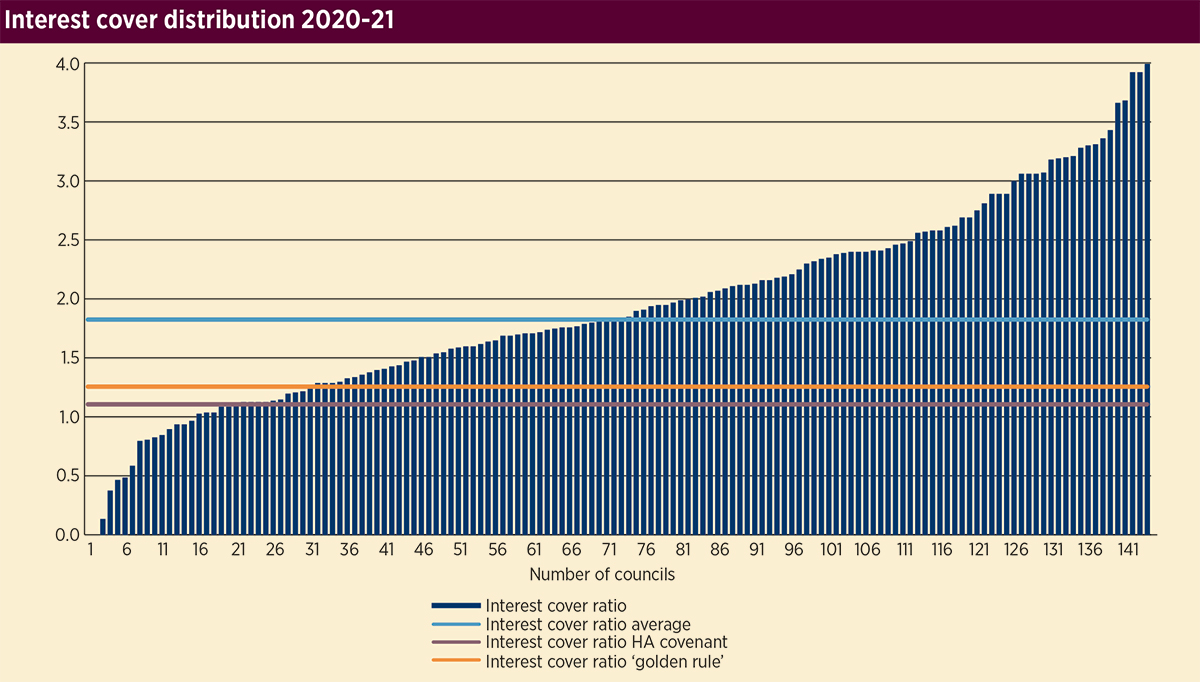

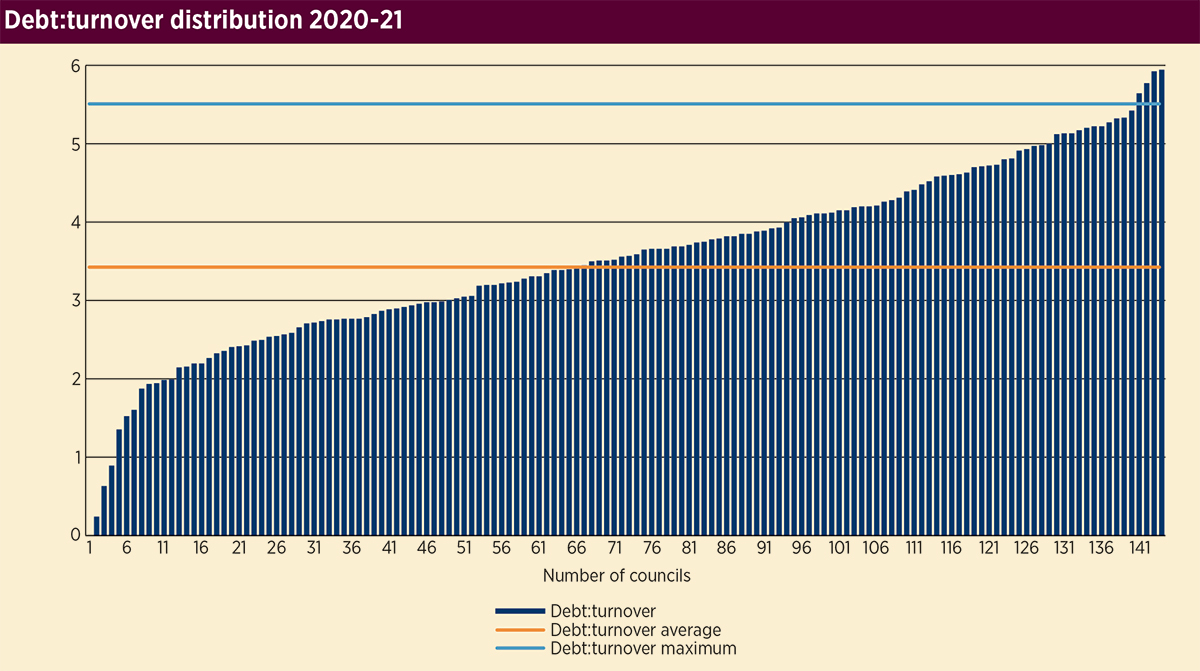

The charts below show the distribution of individual authorities ordered by interest cover and debt:turnover and compared to the minimum, maximum and golden rules of these two metrics. Both charts exclude six ‘outliers’ for each metric, as these would visually distort the chart presentation.

For the debt:turnover chart, just 10 authorities have debt (at 31 March 2021) higher than 5.5x turnover (2020-21 financial year). These authorities tend to be smaller district councils in the south and east of the country where there was a very high level of debt inherited from the self-financing debt settlement of 2012, but are also known to be investing significantly in the development of new homes.

A total of 66 authorities (around one-third of all authorities) have debt:turnover below the national average, suggesting plenty of additional headroom at these authorities to increase borrowing. And if borrowing is increased to provide for new homes (via acquisition or development), such borrowing would tend to increase turnover in future.

For the interest cover chart, we have plotted the distribution against the national average, the golden rule of 1.25 and the theoretical minimum covenant level of 1.10. The picture that emerges is striking.

A total of 80 per cent of authorities ended 2020-21 with interest cover above 1.25. There were 11 authorities where interest cover was below 1.25 but above 1.1. There were 17 authorities with interest cover showing below 1.10, 13 of which were below 1.0.

On the one hand, this distribution is as expected. Some authorities will have more capacity than others, and those authorities investing heavily will be experiencing pressure when it comes to this metric, with a view to increasing net income when new homes are completed, thereby generating additional and future capacity going forward – generally investing in advance of income.

On the other hand, this highlights the question around how local experiences can differ when taking an overall national average approach to analysing the data.

For those authorities between 1.1 and 1.25, resilience to changes in circumstances is potentially reduced in the short term – as any shocks to income (ie losses through voids) or to expenditure (for example through inflationary pressures) could theoretically lead to a need to draw on reserves.

In theory, having interest cover below 1.0 suggests that an authority has a deficit on the HRA and is drawing on reserves. It may be that this is planned and temporary – again, this notion of investing in advance of income generation. There may also be technical reasons for this position – perhaps some authorities are reporting other elements of debt financing as interest costs.

Whatever the rationale locally, if we isolate those authorities where interest cover was below 1.25 and suggest that in the short term their capacity to take on additional debt would be limited, and we focus on those authorities with capacity above the 1.25 golden rule, then we highlight that our estimate of additional capacity to take on interest costs increases from £430m to nearly £500m, an increase of 15 per cent, suggesting capacity for investment up to £13bn.

What about loan-to-value?

We could also apply a similar analysis for loan-to-value, which is usually a hard covenant for housing association lending, however we do continue to come up against the fact that the valuation methodology for council dwellings is in need of review.

Debt (as measured by the Housing Revenue Account capital financing requirement) compared to asset valuations is 27% – still well below the average in the housing association sector and way below the standard housing association lending covenant.

As we have suggested before, the fact that interest cover and debt:turnover are broadly comparable to housing association averages (as per the Regulator of Social Housing’s Global Accounts) while loan-to-value is so much lower than housing associations tends to suggest that council housing is ‘over-valued’ when compared to the underlying cash flow surpluses that are being generated by the assets in operation.

The resource accounting valuation guidance published by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) focuses on a valuation methodology that is based on open market values discounted by a factor that is applied at the regional level.

This guidance was due to be updated so that new discounts to market values would be published to take effect from 2021. However, DLUHC officials are yet to announce a timetable for this update.

Rather than simply focusing on updating discounts, our analysis continues to suggest that a fundamental review of the asset valuation methodology would be advisable now that the debt cap has been removed and authorities are responsible for setting and publishing on their own HRA prudential indicators.

Capacity summary: are there headwinds?

These feel like important findings at a time when local authorities are under increasing pressure to address investment needs, whether these are driven by existing stock (building safety, starting on decarbonisation programmes, decent homes) or by the need for new homes and regeneration.

Our analysis continues to show that, despite there being a small number of authorities investing heavily, and the majority of authorities at least in part delivering new homes through borrowing, that capacity remains strong and largely untapped. Despite the four years of rent cuts when authorities were in general reluctant to invest even when the debt cap was abolished, the amount of capacity in the HRA sector remains high. We have never consistently found this to be less than £10bn and, as the analysis above shows, it is likely to be much higher than this.

When we come to do our analysis for the 2021-22 financial year, we expect to find that the key measures have again strengthened. This is because all the main drivers for capacity moved in the right direction: rents went up by CPI plus one per cent (in the main), pay awards were controlled and interest rates were at a historical low.

Yet there are potential pressures mounting: inflation on supplies, utilities and contractor costs. Clients report to us some really high inflation in these areas, including many contractors being unable to respond to tenders or unwilling to proceed on tender prices submitted just a few weeks previously. Interest rates have increased and are set to increase further.

The level of CPI is likely to be 10 per cent in September and authorities will await with some trepidation the announcement in October of September CPI, the driver for rent increases next April. Given political uncertainty nationally, we do not know whether the government will act to cap rent increases next year. Even without government intervention, we have yet to find an authority client who thinks that their members will put rents up by the full CPI plus one per cent.

The interplay between actual rent increases and cost pressures has the potential to inhibit investment, partly because of uncertainty about where the next pressures are coming from and at what level, and partly because operating surpluses may reduce in the short term, in turn reducing investment capacity.

Nevertheless, we would need to see an ‘across the board’ 10 per cent increase in all operating costs and a rent freeze before we started to see the key capacity metrics approaching the theoretical minimums, maximums and golden rules nationally. There will be a range of factors affecting income and costs in the current and next financial years that suggest capacity might come under pressure, but a ‘doomsday’ scenario of capacity being severely diminished feels a long way off, especially as authorities will be preparing detailed plans to address these pressures in the next few years.

One key factor that is likely to come much more to the fore, however, is the interplay between investing in high-cost existing stock and investing in regeneration and new build, and whether achieving better long-term value by avoiding the former and doing the latter will become an increasing feature of business plans in future.

Sign up for the Social Housing Annual Conference 2022

The Social Housing Annual Conference is the sector’s leading one-day event for senior housing leaders, which delivers the latest insight and best practice in strategic business planning. The conference will provide multiple viewpoints and case studies from a variety of organisations from across the housing spectrum, including leaders in business and local and central government.

Join your peers for a full day of intensive, high-level learning, networking and informed debate addressing the most crucial topics surrounding finance, governance and regulation to help the sector understand and manage the pressures it faces.

Find out more and book your delegate pass here.

RELATED