Tipping point: how has for-profit RP debt evolved?

A number of high-profile debt deals in the past year saw equity-backed RPs gear up their organisations. Sarah Williams investigates how the funding mix for this cohort is evolving as portfolios grow

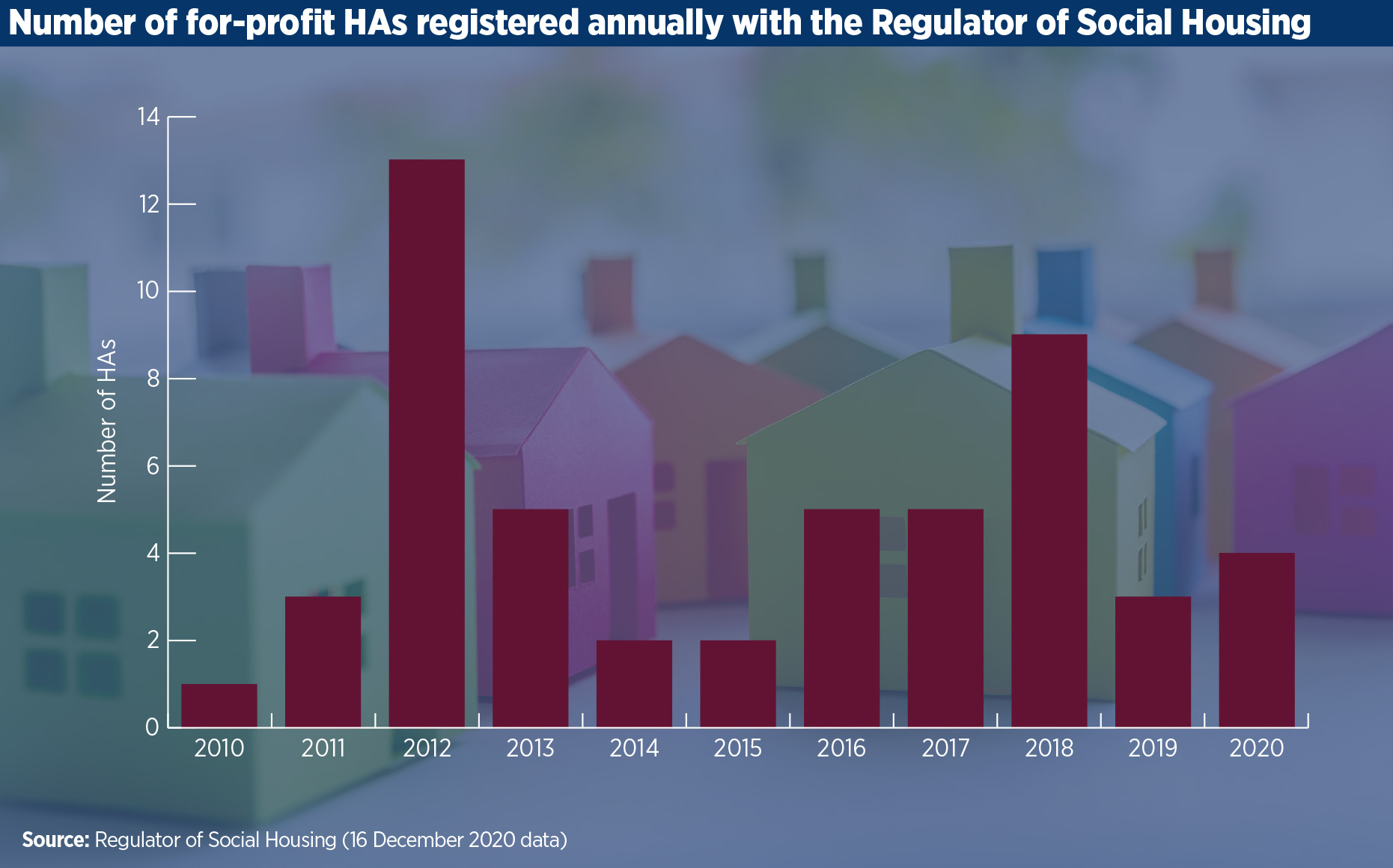

Legislation to allow the registration of for-profit registered providers (RPs) is now more than 12 years old, but it is only in the past three years that private capital has surged into this sub-sector.

Entrances have included the world’s biggest property investor, Blackstone, and the UK’s largest institutional investor, Legal & General (L&G), alongside the establishment of new private and listed funds.

There are now 52 for-profits registered with the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH), with UK investment manager and long-time funder to the sector M&G Investments the latest entrant.

Although the controversy surrounding for-profits has not gone away, their ability to arrive chock-full of capital ready to deploy into developing or acquiring stock has already supported rapid growth.

But as equity-funded activity sprouts into growing volumes of owned stock, a number of for-profits have begun to gear up their portfolios, using these assets to secure debt finance with which to feed further growth. In the past year, in excess of £1bn of debt finance was agreed by a handful of the largest for-profits.

As Phil Jenkins, managing director at Centrus, puts it: “There’s a period of ramp-up in any of these structures where portfolio acquisition is the primary priority in deploying the equity that they’ve raised, but then once you’ve got the stabilised assets in there, depending on the rules of the fund or the REIT [real estate investment trust] in question, gearing up to try and enhance shareholder returns through that route may be an attractive option.”

So what does the debt itself look like? Is it long or short term? Are covenants comparable to not-for-profits? New or familiar products and lenders? The answers are as varied as the organisations themselves – although with some common qualities.

Previous commentary on the for-profit sector has depicted the emergence of three main categories of provider: build-to-rent specialists; house builders seeking to retain Section 106 contributions; and the institutional or investment fund-backed players, which span a range of structures and strategies.

Rob Beiley, partner at Trowers & Hamlins, tells Social Housing that while varied entrants continue to arrive, these three categories remain accurate. He adds: “But what we’re starting to see from the market is that it’s the institutional investors with their RPs that are getting to scale quicker than the other two categories – which is why we are seeing the first debt deals in that segment rather than in the other two sub-sectors.”

Smaller players are gearing up, too, but deals at the institutional end of the market have been by far the most eye-catching during 2020, in some cases bringing first-in-sector approaches into play, from Sage Housing’s £220m commercial mortgage-backed securitisation (CMBS), to Residential Secure Income’s (ReSI) £300m, 45-year deal secured entirely on shared ownership properties.

Here Social Housing looks at how the debt profiles of three major for-profits evolved during 2020.

Sage Housing

Debt:

- £220m – CMBS

- £580m – RCF from syndicate of four lenders

Having delivered more than 2,400 homes, Sage Housing, which received backing from Blackstone in late 2017, is expected to deliver around 3,500 homes next year as it works towards a stated goal of delivering at least 20,000 homes by the end of 2022. All of these homes will be at affordable or social rents, or for shared ownership.

As chief financial officer John Goodey puts it, this rate of growth puts Sage in an “entirely different league” in terms of the number of affordable homes it is delivering annually, even compared with the largest of England’s not-for-profit providers.

“We’ve become a scale provider very quickly compared to the normal genesis of registered providers. Some of that is due to the genuine commitment that Blackstone has made to build this business in the right way, [and] provide stable capital, and expertise.”

Sage, which also counts Regis as minority shareholder, is close to having 12,500 units under contract to be built across its pipeline and existing units, Mr Goodey reveals.

“We have gone from a start-up to a £2bn commitment to social housing in England, in a three-year period.”

This appetite for cash saw the provider list a £220m CMBS on the Irish Stock Exchange in October – a type of transaction not seen in UK social housing before. The securitisation also carries a ‘social’ label, which was accredited by second-party opinion provider Sustainalytics.

Managed and arranged by Deutsche Bank, the securitisation from issuer ‘Sage AR Funding No1 plc’ featured a portfolio of 1,609 properties, across seven tranches of floating-rate senior notes. These ranged from £89.1m of ‘class A’ notes at a coupon of SONIA plus 1.25 per cent, through to £11.1m of subordinated ‘class R’ notes, at a coupon of nine per cent. The notes have a loan term of five years, but Sage has an option to pay costs and end the agreement at an earlier stage.

Mr Goodey says that Sage’s approach of securitising an individual portfolio of properties – as opposed to issuing a bond at the group level, as commonly seen in the non-profit sector – made sense for the current stage in its journey.

“We have high levels of security we can offer in these individual portfolios that are completed, but Sage as an entity is relatively early stage, compared to a G15 provider. Over time what we do may well change because we are continuing to grow and mature.”

The approach may also have brought new investors into the sector, Mr Goodey believes, with the specific structure of the notes making them applicable to “a certain subset of the credit investor spectrum”.

Gadi Jay, managing director – real estate at Blackstone in London, tells Social Housing that the “uniqueness of the deal required a fair amount of investor education”, but that the resulting interest was unprecedented.

“We had about 100 people participate in our global investor call – which is maybe three times more than you would expect to see on a ‘normal’ commercial mortgage-backed security. The investor demand from the get-go was fantastic.”

Significantly, the 1,609 properties used to secure the notes solely comprised rented properties – reflecting a wider strategy at Sage to delineate between its rented and shared ownership properties.

Mr Goodey explains: “We figured out early on that going to potential credit investors with the two stories in one package was going to be a big ask of them to understand so much in a very short period of time, because [the tenures] are different and they have different traits. We decided with Blackstone pretty much from the beginning that we would have essentially the bifurcation set up for long-term financing and for long-term ownership in our RPs.”

Sage’s parent RP predates Blackstone’s involvement in the company, but in December 2019 two further providers were registered with the RSH: Sage Shared Ownership and Sage Rented, with the latter formally named in the CMBS as the parent of the borrower.

As more units are acquired, Sage is likely to put together and securitise further portfolios of properties – including of its shared ownership assets, Mr Goodey says.

He adds that with 3,500 homes set to be delivered next year, that would enable “two bonds’ worth” of issuance volume, based on the recent offering.

Adding to its funding mix, Sage picked up investment partner status with Homes England at the end of 2019. According to Mr Goodey, this enables the provider, which typically acquires its properties through Section 106, to “talk to developers about true additionality in scale”.

Meanwhile, the £220m CMBS complements an existing £580m revolving credit facility (RCF) provided by a syndicate of four lenders first agreed in January 2019 (at £380m) and extended in 2020.

Mr Jay explains: “That effectively is an acquisition facility. It allows us to acquire units in various stages of completion, is supported by a number of large banks and institutional investors and is relatively flexible and allows us to invest and grow the business where we see good opportunity.

“One of the things we value greatly is flexibility and stability, so we want to ensure that we are able to invest where it makes sense, and try not to be governed by limitations of debt or other kinds of considerations.”

This is reflected in the absence of any specific gearing ratio target for Sage, Mr Jay adds.

“We want to ensure that the leverage that the business is taking on is sustainable. So it’s finding the right balance, and it depends really on the ability of the assets to support and the ability of the business to support the financing. We will continually evaluate what the optimal leverage is.”

The extent of Blackstone’s own equity investment in Sage to date is undisclosed, but it runs into the “hundreds of millions of pounds”, Mr Jay acknowledges – and it continues to grow.

Asked whether there is a fixed end date to its investment in Sage, he says: “The funds that have invested in Sage do look to return capital to their investors, so there will come a time where they would look to exit the investment as it were, but there is no hard deadline to that. And Sage homes will remain affordable in perpetuity.

“For now our priority remains as it was at the outset, to bring incremental capital to the affordable housing market and capacity to a sector where traditional registered providers can struggle to keep up with demand.”

ReSI

Debt:

- £300m – 45-year loan from USS (shared ownership)

- £96m – 25-year private placement with Scottish Widows (retirement homes)

- £14m – three-year term loan from NatWest (council housing)

Elsewhere in the for-profit sector, debt taken on during the year looks rather different. The REIT behind ReSI Housing, the for-profit provider registered in 2017, took on an ultra-long £300m loan with pension fund the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) in July, the lender’s first in the sector.

ReSI plc’s facility stands out not only for its 45-year term and the use of covenants based on cash flows rather than loan-to-value, but also the fact that it will be secured exclusively on shared ownership units. Lenders in the broader sector have been slowly coming to terms with the tenure, but in many cases implement a limit on the proportion of security it can constitute. As such the deal is understood to be the first standalone investment grade financing secured against shared ownership.

Ben Fry, fund manager at ReSI plc and its investment advisory Gresham House, tells Social Housing that getting lenders on board with the tenure is “definitely a process”.

“It’s important to explain shared ownership and ensure people fully understand it. But the key difference between the way we finance shared ownership and the way, say, a housing association would do it is that we’re much lower leveraged than a typical housing association is when they are looking at using security,” he says.

ReSI plc’s full-year accounts to 30 September 2020 report loan-to-value of 43 per cent following its initial £34m drawdown from USS, with a targeted gross asset value leverage ratio of 50 per cent as a medium-term target (meaning debt divided by asset value). This refers exclusively to debt finance rather than equity capital, and does not include grant funding accessed through its RP subsidiary’s partnerships with the Greater London Authority and more recently Homes England.

Mr Fry says: “When a typical housing association is looking at using security, they would have an MVST [market value subject to tenancy] asset cover requirement generally of 115 per cent. If we were to convert our 50 per cent leverage on the same basis that’s 200 per cent MVST. So that’s the key difference, and the benefit that bringing new equity into the sector really brings is that it gives you a loss-making equity cushion that you can then use leverage against to help drive capacity of the sector overall.”

ReSI plc will draw the funds over a three-year period with security put into place as schemes are acquired, and will not pay commitment fees on undrawn amounts. It will pay an annual coupon of 0.461 per cent, while the drawn debt also inflates in line with the Retail Price Index (RPI) linked rent on the shared ownership leases until it is paid down, with an annual RPI cap and collar of zero and five per cent respectively. After an interest-only three-year period, the loan will fully amortise over the remaining 42 years.

Mr Fry says that ReSI plc’s focus is “very much on long-dated debt, so in that 25 to 45-year range”.

“Ultimately we are long-term holders of the asset and we want to preserve the cost of debt over as long a period as possible.”

He adds that the team behind ReSI, which includes new owners since March 2020 Gresham House, sees shared ownership as “the right asset to be privately financed in the sector because it’s an asset that will revert back to the private sector over its life as it staircases, which makes it different to social rented that are really perpetual assets in the sector”.

The facility from USS marks the first debt in ReSI plc’s portfolio against shared ownership assets, but it has two loan facilities against other parts of its portfolio. This includes a 25-year private placement with Scottish Widows on its retirement living division, with £96m outstanding, and a three-year, £14m term loan with NatWest in its smaller local authority portfolio.

These contributed to total debt (net of issue costs) of £141m across ReSI plc as a whole as at 2 December, with a weighted average life of 23 years, and a weighted average cost of 2.6 per cent.

Currently, shared ownership represents 19 per cent of the £302m portfolio by value (compared with 11 per cent for council housing and 70 per cent for retirement rental), but the fund has previously expressed ambition for this to reach two-thirds – something Mr Fry says remains the case, albeit at a slightly slower pace this year following the delays in development that have impacted the sector.

2020 also marked the launch of a second RP from the team behind ReSI. Registered in March, ReSI Homes operates independent of ReSI plc and the original RP and, instead of raising money on the stock market, will build a private fund targeted at local authority pension funds, offering a dividend yield of three per cent per annum. This will draw on the expertise of Gresham House, which is experienced in working with these investors.

Mr Fry says: “We believe local authority pension funds are the ideal investor; they have an incredibly long-term horizon and they ultimately want… to facilitate the increase in affordable housing so it is a very natural partner to invest.”

Where ReSI Housing primarily takes on tenanted stock, managed by HA partners, ReSI Homes will forward-fund new development.

The long-term nature of the fund will be comparable to that of ReSI plc, but Mr Fry says that a key difference is that it will not use long-term leverage, and after some short-term borrowing to fund development, will be “pure equity”, in line with the preferences of the investors targeted.

At its launch, the fund set out plans to raise £1.5bn to £2bn over three years, with an aim of raising £400m during the initial fundraising stage, which Mr Fry says “continues to move forwards”. Likewise, where ReSI plc is concerned, Mr Fry says the team maintains “ambitions to grow the fund”, when the share price rises to a level to support this.

Development finance for ‘start-up’ for-profits

Alongside debt deals in the institutional part of the sector, a breed of slightly smaller for-profits, “a bit more start-up in nature”, are also seeking debt, according to Patrick Hawkins, director at Savills Financial Consultants.

“These are people who have maybe got access to equity but it is limited in its capacity, and so what they’re trying to do is bring some debt to gear it up.”

This, he says, involves a “very different pricing dynamic” from the not-for-profit sector, and while some lenders may be familiar to the traditional sector, the teams involved fall into development finance or property market divisions instead.

As well as being more expensive than equivalent lending to not-for-profits might be, the loan terms also differ in view of two key considerations on the part of the lender.

“We tend to see the conversation focusing on two things. One is the people involved and what is their track record in delivering property development, and the second is the exit route for the lender concerned,” Mr Hawkins says.

While loans may share characteristics with non-profits’ RCFs, such as flexibility on drawdown, Mr Hawkins says they tend to be much shorter in length.

“Whereas a traditional RP would borrow a five-year RCF at a competitive margin over LIBOR, development finance might be two or three years.

“This is very specific in terms of the property that it’s funding, and will have a limited shelf life, so that once the properties are built the loan needs to be repaid.”

L&G

Debt:

- £100m – intra-group loan from LGAS

- £175m – development finance from syndicate of three lenders

Legal & General Affordable Homes, which launched as an RP in December 2018 with equity funding from its eponymous investor Legal & General Capital, completed one of the first for-profit debt deals at the start of 2020.

This saw the provider’s ultimate legal parent Legal & General Assurance (LGAS), make a £100m loan to the business through its L&G Retirement division.

The loan is index-linked and secured against the income stream of its pipeline of affordable housing, with half the money tracking RPI (to reflect the rental element of shared ownership) and the rest tied to Consumer Price Index, the index against which social housing rents track after April 2020.

Simon Century, director of build-to-rent and affordable housing at L&G Capital, says that it is “normal, though not as normal as perhaps we’d like it to be”, for L&G to take direct ownership of assets – as opposed to loaning to external borrowers such as housing associations.

“With these types of asset classes we would often like to hold it all ourselves through time, take on board those responsibilities and get the holistic return attached to it through time rather than just the debt investment in isolation.”

The loan is long-term in nature, reflecting the housing assets held by the RP as borrower. Mr Century, whose career history prior to L&G includes roles at TradeRisks and non-profit RP BPHA, describes it as a “pseudo private placement type loan that came through a similar sort of covenant structure, with typical interest cover and gearing covenant requirements”.

This compares with a second, £175m loan agreed around the same time with a syndicate of three lenders, which is shorter-term finance and is held not by the RP but by a self-contained development subsidiary. The lenders are undisclosed but are names mainstream to the non-profit sector, Mr Century says.

He describes this development finance facility as “more bespoke – because it’s quite unusual [within this sector] to find affordable housing development sitting in a company by itself in isolation”.

He adds: “A debate we had with all lenders was ‘how do they feel about this?’ Because it’s not social housing exposure in isolation as it doesn’t have the long-term hold that’s in there as well. It’s not really real estate because this is social housing, it’s very different. It’s closer to structured finance in nature and the truth is it ended up being a bit of a hybrid of all of the above.”

L&G Affordable Homes acquires stock through a mix of Section 106 purchases and, increasingly, direct delivery through land-led approaches subsidised through grant in partnership with Homes England and the Greater London Authority.

It is now closing in on 5,000 units in its pipeline, Mr Century says, with more than 3,000 units already contracted.

“That’s about a billion pounds of assets, and we’re looking to grow that a long, long way – the ambition is to get to 3,000 completed homes a year by 2023, and we are well on the way to doing that.”

With its future scale in mind, the latest accounts for L&G Affordable Homes (the RP, exclusive of the development companies), benchmark the organisation against non-profit providers with more than 10,000 homes when it comes to value for money reporting. The publication (which covers the 2019 calendar year, and so predates the £100m loan), shows a gearing percentage of nil, and a 2020 gearing target of 45 per cent, compared with 46.8 per cent in the median quartile.

Mr Century says that where gearing is concerned, “on the debt side, it has to remain at investment grade – it’s an absolutely pension regulatory insurer objective that we do that”.

This means that the provider would never end up being too highly geared, he says. “It’s about getting the right sensible balance through time where risk-exposure appetite is, at the appropriate level for us as a business.”

Mr Century has previously said that third-party capital could play a part in future delivery. He tells Social Housing that for now it “isn’t directly on the agenda”, but that to hit L&G’s future aspirations “over the coming years, there may be an opportunity to bring third-party capital into the equation”. Whether this is through the existing RP or a separate third party dedicated fund would remain to be seen, he adds.

One development likely to be seen in the nearer term is L&G’s own delineation between its (social and affordable) rented homes and its shared ownership assets, which currently represent around a 60:40 split. Mr Century echoes Sage’s Mr Goodey on this point.

“Different funders have different requirements through time, debt or equity, and trying to find a funder who likes both may not always be the optimum way to scale.”

He adds: “So the thoughts that we and I suspect many others are going through is ‘could you end up with better terms by splitting those assets out into separate vehicles?’ And I think that’s quite likely.”

RELATED