Demonstrating social value needs to be a priority

Sector should focus less on financial metrics, survey says. Robyn Wilson reports. Illustration by Getty

This article was written in partnership with:

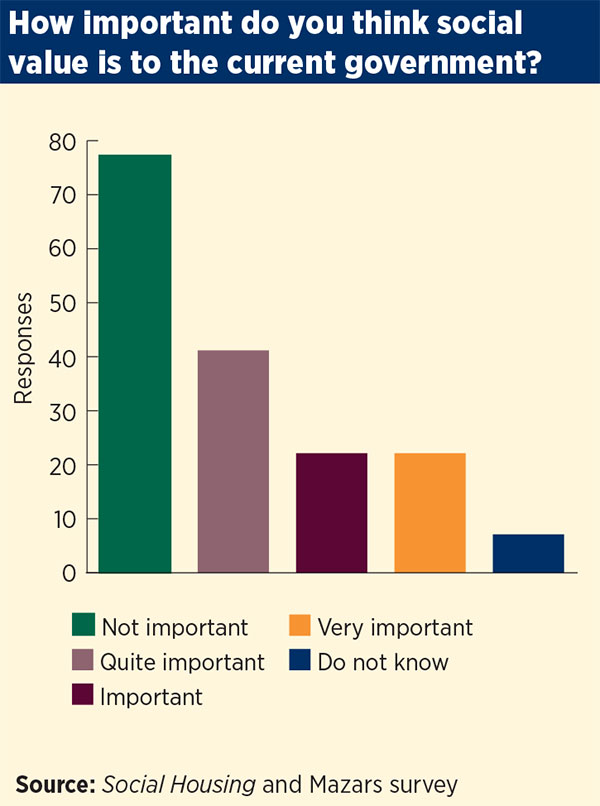

Social housing providers are failing to demonstrate their social value, placing too great a focus on financial metrics, according to a recent sector survey.

The research, conducted by Social Housing in partnership with global accountancy firm Mazars, revealed that nearly 80 per cent of organisations believe that the sector is not doing enough when it comes to demonstrating social value.

Meanwhile, more than 80 per cent of respondents – including directors, managers and officers from housing associations and local authorities – said the sector is focusing too much on financial value and not enough on social impact.

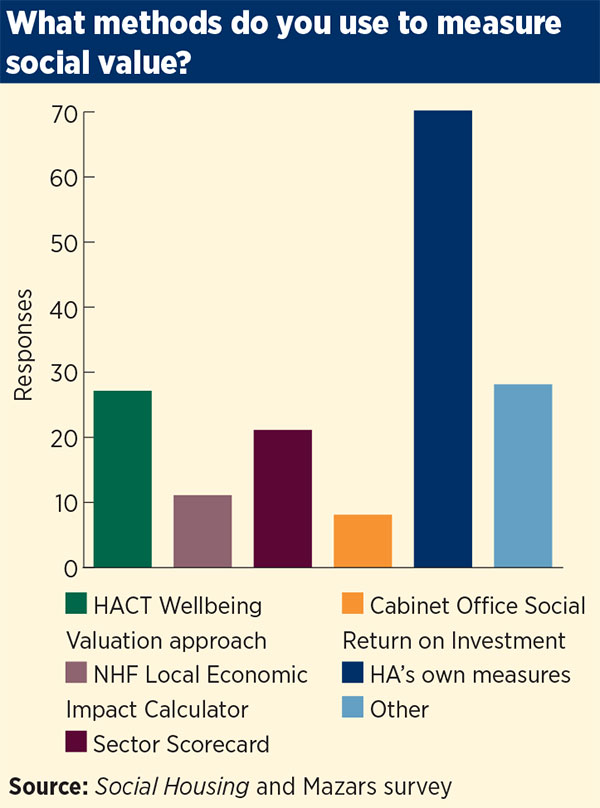

Respondents were also divided over the ways in which they measure social value, which looks at the non-financial impacts the organisation has, especially on the well-being of individuals, communities and the environment.

More than 40 per cent said they use their own measures to quantify social value, while almost one in five said they utilise HACT’s Wellbeing Valuation approach. Other approaches include the National Housing Federation’s Local Economic Impact Calculator, the Sector Scorecard and the Cabinet Office’s Social Return on Investment (SROI).

The results have shone a light on what some would say is a growing imbalance within the sector between financial and social value, and the importance that is placed on the two by individual organisations.

As Vincent Marke, head of housing at Mazars, notes: “With social value, if you spend an extra £100 on a debt advisor or better safety equipment, or better customer satisfaction, how do you value that compared to the financial metrics? Is it really worth getting to 100 per cent customer satisfaction and then diminishing returns?”

Coming at a time of increased awareness of social value post-Grenfell, this research also raises questions about whether increased focus on financial metrics could result in organisations making decisions that are not always better for the tenant.

“Some providers are saying ‘let’s cut these services’ because what’s the benefit now for a housing provider to provide apprenticeships? There’s a social benefit of getting people back to work but they’re not great for their financial metrics,” Mr Marke says.

Echoing this challenge – and despite the inherent not-for-profit nature of the sector that sees it reinvest surpluses – one survey respondent says: “There is too much focus on financial gain [as] opposed to the well-being of residents. We know affordable rent for the majority is not affordable. This is further [exacerbated] by increasing service charges and the inability to have repairs carried out in a timely manner or in some cases, at all. Housing bodies need to do more [and] this quite possibly may need to be enforced by governance.”

Another respondent says: “The commercial priorities, especially of private finance, are increasingly crowding out any social ambitions of providers.”

The survey follows a report by Mazars – Rethinking Social Value – which highlighted similar challenges around defining and measuring social value, particularly at a time when public spending is constrained and organisations are having to find new ways of unlocking resources to improve people’s lives.

A deeper dig into the survey results shows that the reasons given for the sector’s struggle to demonstrate social value are mixed. Many respondents say that the sector can do more to boost communication and PR in this area.

Others, meanwhile, point out the complexities around measuring social value and the impact this has on the sector when it comes to demonstrating how they are achieving it, including calls for a “usable, consistent and widely adopted methodology for measuring and reporting” social value, as well as multiple requests for increased transparency.

Commenting on this perceived failure to demonstrate social value, Mr Marke says: “This is a real problem for the sector because there are pressures on the public purse, with the government and regulator wanting to sweat assets and do the most they can for the public good and yet [providers] are not able to demonstrate social value.”

He also makes the point that there is no requirement by the Regulator of Social Housing for housing providers to report on social value. “I want to see a more equal weighting to financial and non-financial metrics,” he says.

“It’s quite clear that it would be better if there was an equal split of financial and non-financial metrics that would encourage people to consider [social value such as] customer satisfaction and spend money on non-financial areas.”

Still, if non-financial metrics were given equal weighting by the regulator, there would be a need for a more consistent methodology to measure social value, which everyone in the sector could use. But the survey results show that this is a way off from being achieved.

As Mr Marke notes: “What we’re seeing is there is no standard, uniform metric measurement of social value in the sector, as the question that asks what methods are used to measure social value shows” (see graph, above).

“It’s quite good that people are using their own measures, but it doesn’t aid comparability or the ability to audit.”

This is backed up by one respondent, who says: “There are so many different social impact frameworks that comparison is impossible.”

This desire for consistency, however, is reflected in the survey results, with one respondent saying: “[We need to] agree which evaluation framework we are going to use as a sector so we are measuring things in the same way.”

Mr Marke raises the possibility of using an existing framework such as HACT’s Wellbeing Valuation approach (subject to research), while noting the challenges of qualitative versus quantitative measurement and the value various tools and methodologies can offer.

In contrast to this point, one respondent says: “My view is that we need to think more creatively and move away from simply replicating models already in the market.”

They add: “In many cases, social value goes unnoticed because we have not understood the true depth and extent of it because we are too busy running the operation. Social capital is therefore ‘left on the table’ and under-reported.”

Another respondent suggested making better use of technology to measure social value, saying: “Social impact needs to be clearly at the heart of any organisation. An app could measure and demonstrate the social impact between all the organisations. This would encourage competition and maximise value.”

Further complications arise in this regard, however, when considering how many and which non-financial metrics should be measured.

The survey findings show that the majority (40 per cent) of respondents report on between one and three metrics, while nearly a third cover between four and seven. A sizeable 20 per cent look at between eight and 10 metrics.

As for which metrics are being reported, environment and carbon neutrality are flagged. Employment, staff and health and well-being also come up.

One respondent says that they “flex” their metrics based on the annual assessments they carry out around their impact on their client, workforce and community.

Customer satisfaction, though, was by far the most frequently cited metric. Most of the respondents say they validate this through surveys and some stress that the surveys must be independent. On this apparent focus on customer satisfaction, Mr Marke makes the point that to get a well-balanced measure of social value across the sector, “we need to make sure we are not just talking about one measure”.

But he adds that these metrics will vary depending on the size, location and make-up of the housing provider: “Employment services are more important to some areas than others, for example. We have some clients who specialise in supported housing, which costs more than general needs [units] to provide, so the financial metrics are worse.”

Interestingly, the findings show that the respondents are more in favour of embracing league tables than not (44 per cent in favour, compared with 36 per cent who say no, and 19 per cent who say they do not know).

This contrasts somewhat to the pushback seen earlier this year, after the government’s Social Housing Green Paper mooted the use of league tables within the sector.

At the time, industry sources raised concerns over how such a measurement may exacerbate stigma around social housing, particularly for tenants living in homes that were ranked poorly.

In that instance, tenants would be unable to move but would still have to live in a property with a bad reputation.

In terms of how social housing providers go about reporting to stakeholders that they are delivering social value, the majority of respondents (43 per cent) say they do this in a separate note to their accounts.

A third, meanwhile, say they do it through their financial statements, and 24 per cent say they do it through “other” means. Alarmingly, for many of the 24 per cent this includes not reporting to their stakeholders at all.

This latter figure becomes all the more interesting after reading a response from one survey participant, who says that by “involving stakeholders in strategic decisions and changes in policy”, the sector would be better able to demonstrate its social value and better shape “how and what to measure in respect of adding social value”.

In other words, by engaging and including stakeholders in the reporting process, both the organisation and its tenants would be better off.

RELATED