The PWLB has priced itself out of the local authority market

There are alternatives to the PWLB – but all bring risk, writes Stephen Kitching

The Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) has been the main source of borrowing for UK local authorities over the past decade, and it is easy to see why. It has multiple structures, a wide range of maturities and transparent interest rates, at a reasonable margin over central government’s own borrowing costs.

This is why HM Treasury’s decision in October to increase the margin over gilts by an extra one per cent has caused so much consternation in the sector.

The impact has been immediate. Local authorities have delayed long-term borrowing decisions as some wait to see if the Treasury changes course again, while others engage with alternative lenders who may lend at lower rates than the new PWLB margin of +180 basis points (bps) over gilts. A small number which have large contractual capital payments due soon have taken funding immediately.

The Treasury was clear in its covering letter that the increase in margin was a reaction to total outstanding PWLB borrowing nearing the statutory limit, following an acceleration in borrowing as gilt yields hit record lows. The unspoken part of this was that some of this borrowing had been undertaken by councils in order to invest in commercial enterprises to support services with the associated income, rather than purely service-based projects.

It will disappoint many that the Treasury has chosen this blanket approach to deter local authorities from using the PWLB as the primary source of long-term borrowing. The timing of the announcement may have been significant. With the possibility of yields falling further in the event of a no-deal Brexit at the end of October, the Treasury may have been pre-empting a further round of borrowing. Equally, if a deal were to begin to take shape, it may fear a sudden rush by authorities wishing to borrow before gilt yields rise.

Although the rationale for the increase in PWLB rates is clear, the unintended consequences will be significant. Until very recently, the ability for local authorities to build more social housing was constrained by the limit each housing authority had on its total housing debt – the Housing Revenue Account cap. When this limit was lifted last year, it was with the explicit intention of kick-starting council housebuilding. Councils responded to this with ambitious housing programmes, all budgeted based on PWLB rates.

The increase in margin may call into question the affordability of some of these housing schemes – surely not the government’s intention. The self-financing regime further complicates the picture; the costs of housing, including debt interest costs, must be met by income from housing so the higher rate means that there is less revenue to spend on other housing-related costs.

The impact of the PWLB on housing doesn’t stop at council provision of social housing. In recent years councils have set up their own housing companies, allowing them to provide a broader range of tenures, such as shared ownership, affordable housing, and homes for market rent and sale. With these projects reliant on funding from the parent authority, the increase in funding costs will stretch the ability of councils to supply the specific types of housing that meet the local requirement.

Furthermore, partnerships between local authorities and housing associations/registered providers that have relied on funding from the local authority at PWLB rates will now have to be re-examined and re-costed. With some schemes already being paused for review, it is not just local authority housing that will be impacted – some registered providers’ business plans will be affected, putting the delivery of housing in some hard-to-supply places at risk.

However, local authorities are unlikely to give up on their housing plans or their intentions to improve the infrastructure of their local areas. Although the PWLB has effectively priced itself out of the local authority market, there are alternatives that councils will turn to – some immediately, others requiring more long-term engagement, and all presenting some form of risk.

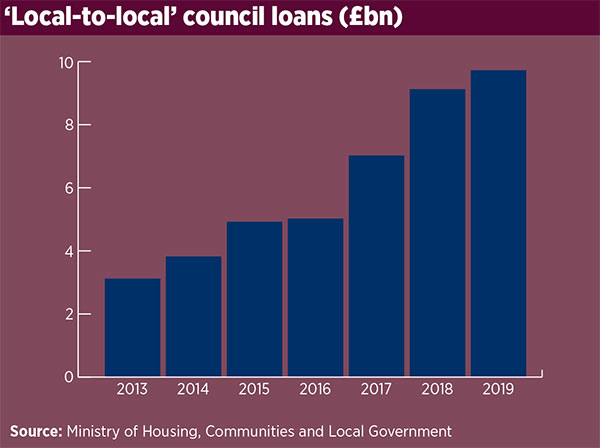

In the first instance, local authorities will look to borrow from other councils that have surplus cash balances. The ‘local-to-local’ market, facilitated by intermediaries such as dealing platforms, has grown from £3.1bn in 2013 to £9.7bn in 2019 as local authority lenders have looked to avoid the credit risk associated with banks, while borrowers have taken advantage of historically low short-term rates.

This trend is likely to continue, as councils avoid the new PWLB margin. However, as the duration of local authority loans generally ranges from one to 12 months, councils that rely on this type of funding will see an increased interest rate and refinancing risk compared with long-term, fixed-rate debt.

In the longer term, authorities will look to limit their interest rate risk, and private sector funders have been quick to examine their options for lending into the sector since the Treasury’s announcement. Previously it was difficult for the private sector to compete with a rate of 80 bps over gilts, but the new, higher margin will mean that as well as offering different structures such as forward starts, lenders can compete on price.

These sorts of bilateral agreements, if properly arranged, will be sufficient for smaller organisations looking for rates below the PWLB’s. However, larger or more ambitious councils are likely to look to capital markets for large-scale funding. Up to now, individual bond issues have been unusual, but given the size of some council borrowing requirements, more may look to tap markets. This is likely to lead to a further differentiation in the perception of local authority credit, and different borrowers will pay different rates of interest as a result.

It may be that this change in perception was intentional when the Treasury increased the rate, or it may be another consequence of applying a blunt instrument to a very real issue. Either way, local authorities that wish to continue to increase their supply of housing will need to work with more than just the PWLB to meet their ambitions.

Stephen Kitching, client director, Arlingclose

Social Housing special reports

Each month Social Housing focuses on a specific aspect of housing finance and collates and scrutinises the data for hundreds of housing organisations.

The reports below contain unparalleled commentary and analysis along with detailed sortable and searchable data tables.

Unit costs 2019 Our analysis of data from the English regulator has found that unit costs have risen among all types of housing association, with overall maintenance costs seeing the highest weighted average increase of nearly seven per cent

Impairment 2019 Housing associations’ impairments rise almost 40% in a year, driven by fire safety costs, contractor insolvencies and reduced land values

Global accounts 2018/19 Housing associations’ surplus for the year before tax decreased by five per cent to £3.76bn, driven by a 6.6 per cent drop in England

Affordable rent profile 2018/19 The level of affordable lettings dropped for the third year in a row

Staff pay Data from audited accounts of 206 housing associations shows that average staff pay in 2018/19 was £31,787 – a rise of 3.2 per cent over a 12-month period

Professionals’ league Our exclusive professionals’ league finds that activity continued apace in 2019, when housing associations increasingly looked to private placements

Sales proceeds Despite a 10 per cent rise in housing associations’ income from development sales in the last financial year, sales revenue is likely to remain flat over the coming years as a result of the property market downturn

Capital commitments The total capital commitments of 200 housing associations rose by 15 per cent in the past year, analysis by Social Housing has found

Reliance on sales surplus Social Housing finds that the total sales surplus of 150 English registered providers has dropped by nearly 10 per cent, as a result of lower market sales surplus

Stock dispersal How many council areas does your housing association operate in? How concentrated is its stock?

Accounts digest 2018/19 How does your housing association’s finances compare to others?

Housing Revenue Account part two How do councils compare in their 2018/19 Housing Revenue Account positions? Steve Partridge of Savills takes an in-depth look

Diversification of income We look at how housing associations are diversifying their income, and finds that they made 10.3 per cent more revenue from shared ownership and non-social housing activity

Impairment 2017/18 Social Housing takes a close look at the accounts of the 130 largest housing associations, and finds that impairments rose by nearly a third to £78.4m in 2018

Global accounts Social Housing’s analysis of the sector’s global accounts finds that housing associations’ pre-tax surplus fell last year – driven by drops in England, Scotland and Wales (August 2019)

Affordable rent profile We find that the number of affordable rent lettings recorded last year by housing associations in England has dropped for the second year in a row, suggesting that the sector is shifting away from the tenure

Capital commitments We scrutinise the capital commitments of the 208 largest housing associations in the UK (June 2019)

Housing Revenue Account part one Steve Partridge of Savills takes a look at the financial factors councils should consider in their Housing Revenue Account business planning (May 2019)

Reliance on sales surplus Our analysis reveals that profits form 42 per cent of 150 English housing associations’ total surplus (April 2019)

Sales proceeds We look at housing associations’ build-for-sale income and find a two per cent increase in 2017/18 (March 2019)

Shared ownership sales England, excluding London, has seen a four per cent rise in shared ownership sales – much lower than last year’s 16 per cent increase (February 2019)

Stock dispersal We show that housing associations’ general needs stock is becoming more concentrated within their local authority areas (January 2019)

RELATED