Cross-sector doubt over government’s levelling-up non-decent rented homes ‘mission’

Is the Levelling Up White Paper’s promise to halve the number of non-decent rented homes by 2030 achievable? James Twomey reports

Scanning the government’s Levelling Up White Paper in February, one could be forgiven for thinking that housing had been forgotten. Amid the potted history of 15th century Renaissance, there were some scattered references to revamping sector mechanisms, such as scrapping the 80/20 rule around regional funding in the UK and a restructuring of Homes England.

But, of 12 core “missions” set out by the paper, only one related to housing, stating: “By 2030, renters will have a secure path to ownership, with the number of first-time buyers increasing in all areas; and the government’s ambition is for the number of non-decent rented homes to have fallen by 50 per cent, with the biggest improvements in the lowest-performing areas.”

The UK has a huge number of ‘non-decent homes’. These do not meet the Decent Homes Standard (DHS), defined as being free of Category 1 hazards, in a reasonable state of repair, with reasonably modern facilities and services, and providing a reasonable degree of thermal comfort. The DHS was published in 2006 and is undergoing a review, expected to be redefined by summer 2022. The standard is legally binding for social landlords only, but the white paper pledges to consult on introducing this to the private rented sector for the first time, alongside cracking down on ‘rogue landlords’.

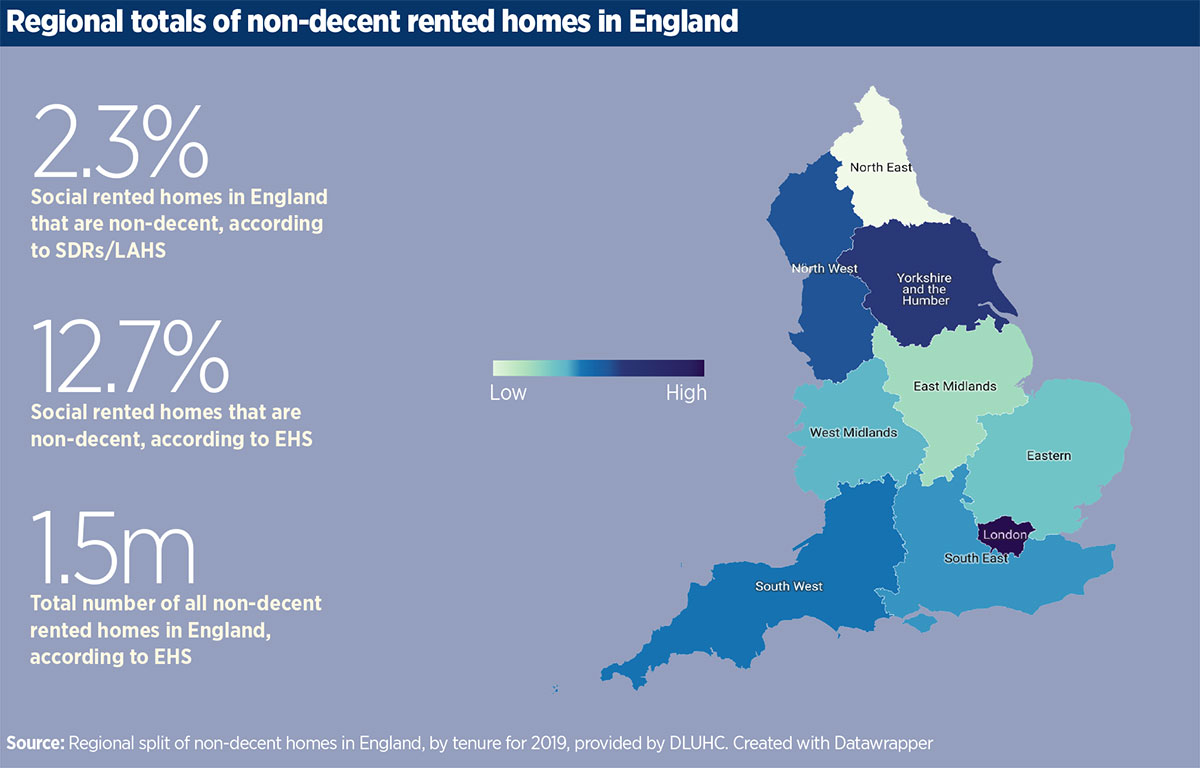

Mandatory data returns made by social landlords put the non-decent homes problem at a much lower figure than the annual government English Housing Survey (EHS).

The combination of private registered providers’ Statistical Data Returns (SDRs), managed by the Regulator of Social Housing, and Local Authority Housing Statistics (LAHS) show that of all social rented homes in England, 2.3 per cent are non-decent. The EHS puts the percentage of non-decent social rented homes at 12.7 per cent, or 517,000 homes. However, the latest data for this is 2020.

The LAHS landlord returns figures for non-decent homes are based on the number of properties that local authorities are directly aware of and do not include cases where tenants have refused improvement work. The EHS figures are based on a physical inspection of a random sample of the whole housing stock, and tenants in social rented properties identified by the EHS as non-decent may not have made their landlord aware of the issues with their property.

This means reported levels of decent homes have been consistently lower in LAHS and the SDRs than on the EHS.

The EHS also includes rented homes from the private sector, of which 21 per cent, or just over one million, are expected to be non-decent. This means that the number of all non-decent rented homes in England is around 1.5 million.

The number of homes that need repairs in tandem with the lack of money or local authority resources to tackle the issue has drawn widespread doubt over the ability to hit this government target.

In April, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC) released a report on the state of rented homes in the UK. It said that local authorities did not have the capacity to enforce the Decent Homes Standard, nor did the government have the data to understand the scale of the problem.

One section of the report said: “The National Residential Landlords Association told us that a lack of resources and capacity also constrains local authorities’ use of enforcement powers, with some taking a very light-touch approach. Only 10 landlords and letting agents have been banned by local authorities since 2016, and some councils inspect as little as 0.1 per cent of their privately rented properties.”

Rachael Williamson, head of policy research at the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH), says: “It’s unrealistic to think, here in 2022, that we’re going to get there reducing [non-decent homes] for the private rented sector [PRS] in that timeframe without not just funding, but legislation to make it happen. Because, if it’s guidance, is it really going to have the weight? But if it’s legislation, how are you going to enforce it?

“And obviously the PAC report… highlighted issues around enforcement with very, very small teams and effectively a kind of postcode lottery. And we know there’s a really big issue across the sector on recruitment and retention and skills.

“We’re finding as we’re talking to members, increasingly, recruitment and retention and skills are moving up the risk register.”

Landlord register

One of the ways in which the government seeks to improve the rented experience and meet this mission is to establish a national landlord register.

Newham Council was the first local authority in England to adopt a landlord register, in 2013, and says it has 1,100 prosecutions against criminal landlords and has recovered £2.5m in unpaid council tax owed by landlords.

Newham says the government had not made it clear to local authorities what the new Decent Homes Standard will consist of.

In Newham, the main standard used for enforcing property conditions in the PRS is the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS). The council takes enforcement action against landlords of properties where HHSRS Category 1 or high-scoring Category 2 hazards are present, or where the terms of the property licence are not met.

A Newham Council spokesperson says: “Our analysis suggests that around 17,000 PRS homes in Newham may have Category 1 and 2 hazards. Tackling this requires compliance inspections and enforcement staff. When the other criteria of the DHS are taken into account, then this would require appropriate resources to achieve that goal. We hold our own register of just over 40,000 property licences granted within the borough. Although this is not used to enforce DHS it is a vital tool that is used daily to assist with identifying poor properties that require enforcement action via HHSRS and other powers.

“Our analysis, based on inspections and modelling, indicates that seven per cent of private rented properties inspected have Category 1 hazards and 21 per cent have Category 2 hazards. This is in part due to the prevalence of older Victorian and Edwardian properties in the PRS. The council has a significant programme of improvement under way in its owned social housing, and has a £184m budget allocation for works to improve existing properties, including fire safety works and works to improve energy efficiency and reduce fuel poverty.”

Newham Council gave an idea of how long repairs could take, although they are varied in each property, with works to repair a defective window or fix a handrail to a staircase typically achievable within one month. However, a property requiring an electrical rewire, replacement heating system and damp-proofing works could take more than six months.

National picture

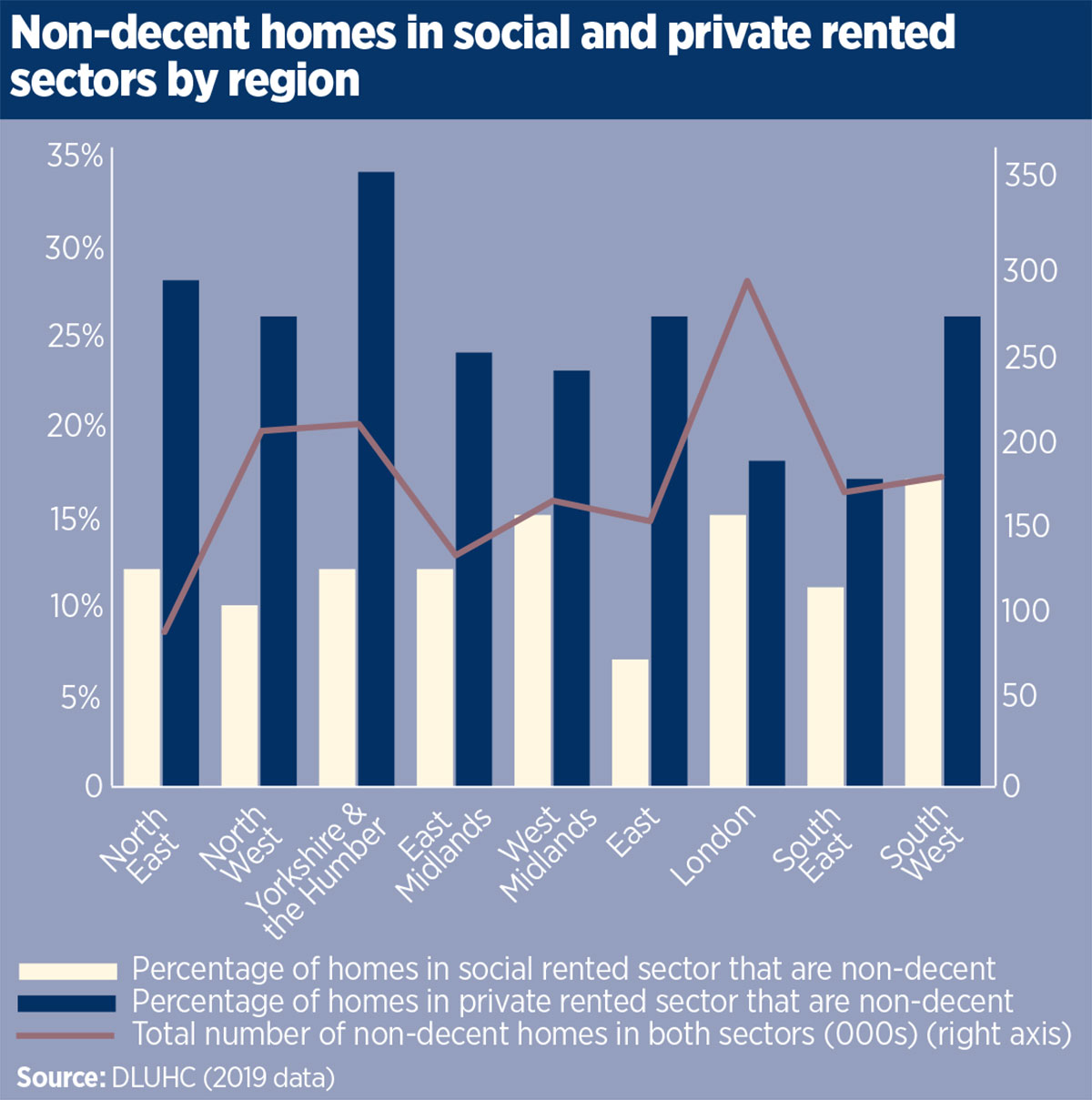

Nationally, the picture of non-decent homes is varied, with the PAC report citing a proportion of privately rented properties with Category 1 hazards ranging from nine per cent in London to 21 per cent in Yorkshire and the Humber.

A Local Government Association (LGA) spokesperson tells Social Housing: “It is unacceptable that nearly 600,000 private rented homes in England, about 13 per cent, have been classed as a serious threat to health and safety, while nearly a quarter are non-decent. The LGA would therefore welcome stronger enforcement powers for councils, underpinned by comprehensive reforms in the forthcoming PRS White Paper, to raise the standards in the PRS and reassure tenants.

“The private rented sector is a part of the solution to meet the housing needs of communities, but councils must also be given sufficient investment and powers to deliver more high-quality, sustainable and affordable homes and we are pleased to see the Levelling Up White Paper acknowledge the need to support the delivery of council homes.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) could not confirm how much it expects the mission to cost, nor whether any additional funds would be supplied to achieve it.

A DLUHC spokesperson does tell Social Housing: “Poor-quality housing is indefensible, so we’re introducing legislation to make sure housing associations and landlords live up to their responsibilities. We will name and shame landlords who fail to meet living standards and provide a direct channel to government for tenants with concerns, by establishing a new resident panel. We’re also inviting social tenants from across England to share their experiences with us to shape our reforms for driving up standards in the sector.”

At present, the magnitude of the task and costs appear too much to meet the government’s target. Eloise Shepherd, strategic lead for housing and planning at London Councils, tells Social Housing: “While we welcome the new commitment from government to reduce non-decent homes in the PRS, it is imperative that this new standard in the PRS is properly enforced and councils have proper support and capacity in order for this to be effective. Incentivising and supporting landlords, and investing in more capacity, skills and resource within boroughs to inspect properties, are crucial to delivering on this commitment. Alongside this, we must ensure that the costs of improvements are not met by tenants.

“In London, around 20 per cent of the PRS is non-decent, slightly higher than the national average. This is likely to be due to the larger numbers of high-rise and leasehold accommodation, and mixed-tenure buildings, in the capital. However, with new building safety measures in place and the growing net zero agenda, the definition of what a non-decent home is now needs to be updated as well. This is a real opportunity to commit to London’s environmental future by building towards net zero.”

Further concern has been aired on how the government’s objective may impact the social housing sector. As a more established regulated group of landlords, registered providers might be an easy target for the government to pressure into increasing their home upgrades and decency levels.

Competing costs

While all providers hopefully agree that every home they own should be decent already, they have many competing costs from government legislation to contend with, such as meeting net zero targets and building safety works.

A spokesperson for the G15, a group of London’s largest housing associations, tells Social Housing: “This year, members have invested almost £900m in improvement works and repairs. This included £350m of investment to install 10,500 new kitchens and 21,000 new bathrooms and windows. The new Decent Homes Standard should link to other government strategies, legislative changes and regulation concerning property management.

“Clearly, meeting our priority of continuing to invest significant resources to improve existing homes comes at the same time as a number of other challenges facing all providers, including building safety and decarbonisation. We are also determined to continue building new affordable homes to help tackle the housing crisis, including issues such as overcrowding.”

Fears over costs of the building safety crisis being passed onto social renters have been made clear by the sector and the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee, and an improved Decent Homes Standard could add to concerns.

Ms Williamson at the CIH adds: “What we don’t want is to see that being passed on, particularly while we’re in a cost of living crisis, [through] really, really high rents.

“But if we can get it right, and particularly the energy efficiency, if we can really try and tackle that and start reducing the cost of people’s heating bills, start reducing the costs on the NHS from poor-quality housing or cold housing, if we can look at it in a holistic, fiscal model sense, then I suppose that’s the challenge of what baseline is some of this funding coming from?

“And that’s where we need government to look across to see what does levelling up really mean?”

RELATED