How social housing is leading ESG into a post-COVID-19 world

Social housing could become the UK’s leader in its approach to ESG. How important is this to funders? Luke Cross reports

UK social housing is leading the way in efforts to report collectively on its environmental, social and governance (ESG) credentials, according to the Impact Investing Institute. A consultation to create a standardised approach to reporting ESG – led by consultancy The Good Economy and backed by housing associations (HAs), investors, advisory and law firms – has started the conversation at a sector-wide level. At best, it may result in a practitioner-led governance body to own the standard.

The social housing and ESG working group is not alone in promoting the social value of the sector. But this initiative is more directly aimed at creating a common language with investors at home and abroad, with qualitative and quantitative themes that are aligned to international frameworks and standards.

Olivia Dickson, board member and lead expert at the Impact Investing Institute, which is one of the partners of the working group, describes it as a “grass roots, bottom-up initiative from real people in the field”.

“This has the potential to be the first ESG reporting standard that has widespread adoption in a sector in the UK,” says Ms Dickson, whose board roles have also spanned the Financial Reporting Council, Royal London and Canada Life, among others.

Sarah Forster, chief executive of The Good Economy, says it has engaged with hundreds of individuals and organisations ranging from residents, tenant associations, small and large HAs, and investors of all types.

“The overwhelming view is that this ESG framework is useful and timely and provides a well-designed voluntary ESG reporting standard for both housing associations and investors,” she says.

There will be an updated version of the ESG criteria in the autumn, along with a feedback statement, and the group is discussing forming a group of ‘early adopters’ made up of HAs and investors.

One of the drivers for the social housing initiative was feedback from funders that ESG factors would likely form a more fundamental role in the credit process underpinning future investment decisions – with one pension fund saying these could become as important as financial reporting.

However, the focus on ESG also comes in the year that HAs are signing off 30-year business plans to 2050 – the UK’s net zero carbon target year. Consultancy Savills has estimated that target would cost £17,000 per home on average. That would mean a bill of £51bn across three million homes.

“The green agenda needs to be funded somehow,” says Will Perry, director of strategy at the Regulator of Social Housing. “But that funding would need a return. And as long as rents remain restricted, the amount you can generate for any property is not going to change.”

There is little doubt that climate change has been front and centre in the rise of ESG.

“There is a consensus now that you cannot make a reasonable assessment of the value of a security or an investment without assessing its ESG – you simply can’t figure out if it’s a good or bad investment,” says Jamie Broderick, former head of UBS Wealth Management in the UK, and now a board member of the Impact Investing Institute. “There’s an inevitability about this – around the world, all professional investors are taking this into account.”

He adds that the COVID-19 pandemic “has reminded people that this is not just about climate change”, and that it has added a greater social dimension.

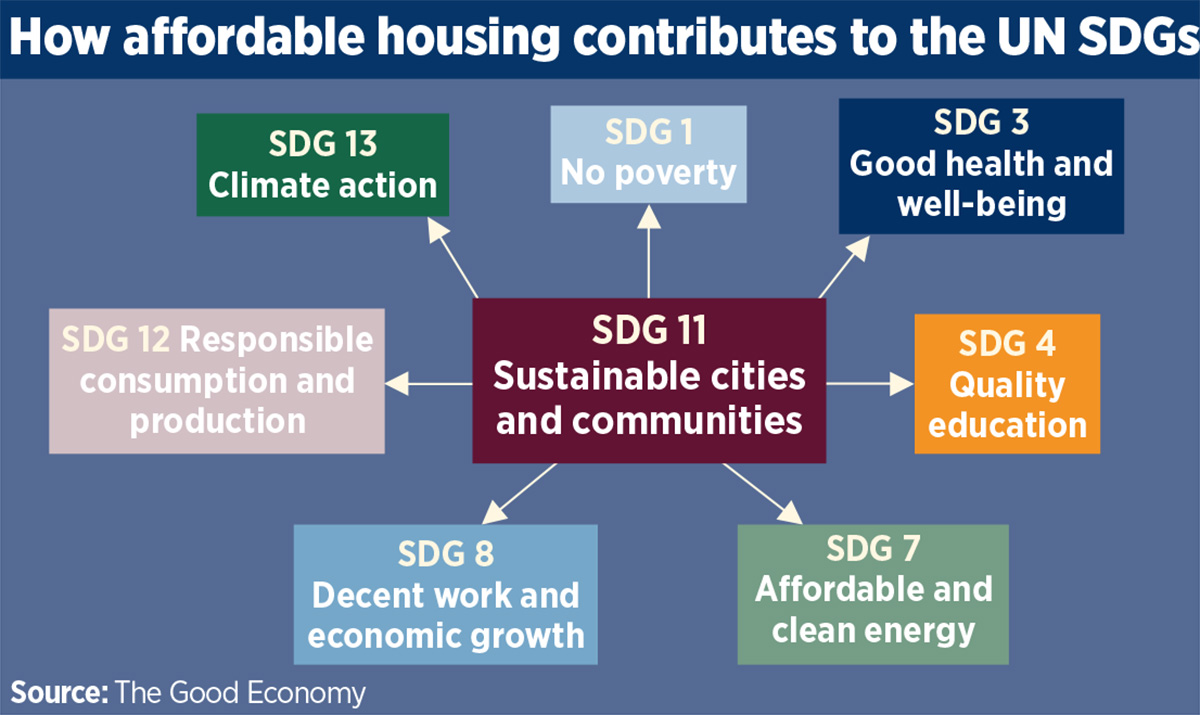

Ms Dickson says the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) “really did focus people’s minds”, with a recognition that private capital is needed to help deliver. She adds the pandemic has given people time “to reflect and think about the interconnection of our world, and the sustainability of the world in terms of SDGs”.

Hannah Marshall, head of UK funds at CBRE Global Investors – which launched a £250m, ESG-focused affordable housing equity fund last year – says she has seen ESG move from being a performance metric “used by select or niche investors” to a mainstream consideration.

Green and sustainable finance is already building momentum in social housing. Piers Williamson, chief executive at The Housing Finance Corporation – which has previously raised green financing via the European Investment Bank – says it will be a major area of focus for the bond aggregator, adding that ESG “will become a hygiene factor very quickly now”.

This is on display at the Bank of England level. In early July, Sam Woods, deputy governor of prudential regulation and chief executive of the Prudential Regulation Authority, wrote to banks, building societies and major investment firms saying climate change “represents a material financial risk to regulated firms and the financial system”.

He wrote: “Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic is a present risk and an understandable priority for firms, minimising the future risks from climate change also requires action now.”

ESG has been in and around the sector in different guises for a number of years, from Cross Keys Homes issuing the first HA ‘green’ bond, to the likes of Blackrock, Blackstone and others citing ESG as part of the reason for entering the sector, to aggregator MORhomes achieving ‘social bond principles’ and Clarion issuing the first sustainable own-name bond.

However, people involved believe that a sector-wide approach could resonate.

“It needs a collective effort that’s properly resourced to help that conversation and to come out with standards with an appropriate degree of integrity and realistic degree of implementation, which isn’t easy,” Ms Dickson says.

Marcos Navarro, a director in NatWest’s housing finance team, writes in an online piece for Social Housing that “not incorporating ESG will impact long-term success for organisations both in terms of financial returns, reputation and having positive social impact”.

Mr Broderick says this addresses a need to facilitate a “meeting of minds between investee and investor”, with a “coherent convergence of expectation on both sides”.

Beyond the green agenda, it is also about “helping others to discover” what everyone in the sector has known for decades – that housing associations generate social value.

“Most of the market just sees the social housing sector as a financial investment,” Mr Broderick says. “So much social value within housing associations just does not get considered by the market. This is a way for the social housing sector to articulate in a more visible way the social value they have been creating.”

Or as Dr Mathias Hain, managing director of European advisory firm Ritterwald – which created a pan-European Certified Sustainable Housing Label and advised on the ESG social housing criteria – puts it, the standardisation would act as a “beacon” to the investor community.

“If you’re looking at sustainable investments, you can’t pass by the housing sector,” he adds.

Mr Perry – who has spent a number of years engaging with new entrants – recognises the importance of having something consistent to “point at” for investors.

While he suggests that there may be some risk of a “proliferation of metrics” at present – including potential key performance indicators within the government’s Social Housing White Paper expected in the autumn – he adds that it may also be something that works the other way, should this become the standardised set.

“Investors need to have these opportunities presented to them in a way they understand. The challenge for RPs is getting into that kind of mindset.”

Mr Williamson goes further: “I think the sector needs to get its act together around a defined governance code, because I think that is a short cut to answering a significant proportion of this.”

From another funder perspective, Ms Marshall explains that there are “multiple unique systems for measuring ESG, making it difficult to accurately compare and assess performance”.

Common standards can also help address the issue of ‘greenwashing’, which Mr Broderick says is another phrase for misrepresentation of ESG-linked outputs.

The work around ESG has, perhaps unexpectedly, segued into a further conversation about impact investing and equity investment in social and affordable housing. There is an awareness of the concern over equity investment in affordable housing, highlighted in Social Housing’s June edition and primed as a debate at the Social Housing Finance Conference in September.

Mr Broderick says: “We have to make sure that risk is appropriately distributed among the parties. That is what this is all about.”

Shamez Alibhai, head of community housing at Man Global Private Markets – part of a hedge fund that launched an equity-driven impact investing housing strategy – says: “By definition equity is difficult to invest directly into the HA sector or within the council sector.”

One of the lessons of the wave of equity investment in real estate investment trusts and specialised supported housing is “to think more about all the stakeholders that are involved”, he says. “It’s not just about who you are helping, but also about all the other stakeholders and their intentionality.”

Others have been able to deploy capital into social housing – including the likes of Sage and Legal & General Affordable Homes – which Mr Alibhai says is “the market signalling that this is where it is possible to deliver an appropriate strategy to deliver returns in line with fiduciary expectations of pension capital”.

He adds: “You can’t increase returns in this sector – the revenue line is effectively constrained, because you are at 80 per cent of market rents or at the [Local Housing Allowance]. Everyone pretty much should be able to deliver the same return. All that changes is how much social, affordable or shared ownership you are doing.”

Mr Alibhai agrees that there should also be a move away from self-reporting on impact, so that impact is audited similarly to financial outcomes. He says that he would like the regulator to promote responsible impact investing.

Mr Perry says: “It’s quite clear from the fact the sector keeps raising debt that debt capacity is not exhausted. From an investment point of view, there are good reasons why you might think equity would be a good idea – the returns on equity are potentially higher. You would have to look at what the sustainability of those returns is.

“It’s not to say you couldn’t have social housing paying equity returns, but those returns will be leaving and would not be reinvested. But it’s not black and white – genuine long-term equity investment in the sector could provide a sustainable model. It is early days, and is not fully tested.”

Mr Broderick says certain types of investors, such as family offices, wealth managers and high net worth individuals “are more flexible when it comes to values-based financial judgements”.

Institutional investors like pension funds and insurance companies are more constrained by the returns they need to make, he argues. “A lot of [pension funds] will say social housing does not yield a high enough return for us. But if you put in the effort and analysis, it’s not a high yield but it is low risk – so on a risk-adjusted basis it makes sense.”

Mr Alibhai points to the pension funds’ fiduciary duty to pensioners. But he says that a long-term view of 10 years or more, along with well-managed properties, means the social and financial returns are “positively related”.

He says that investors should consider “how scalable it is in some areas, for example homelessness”, adding that “there are certain areas that are more amenable to pension capital than others, and at scale”.

The sector’s equity debate will no doubt continue. But despite the general disruption caused by COVID-19, the appetite for both ESG and impact investments “is only accelerating”, according to Ms Marshall. “We have had more investor queries in the first half of 2020 than we did throughout 2019, and we anticipate that this trend will only continue.”

There is also likely to be a rethink of the types of homes being delivered, a move away in the real estate world from “micro-living” and a refocus towards the people on the frontline who serve communities and “keep the machinery going”, according to Mr Alibhai.

He believes this will be a political narrative, but one that is also shared by investors. It is supported by an in-depth review of the global implications of COVID-19 on future focus on ESG risk, published in late June by ratings agency Moody’s.

It says: “Depending on the trajectory of the economic recovery, inequalities associated with other public social issues, including education, access to basic infrastructure and housing, may emerge and warrant greater governmental attention.”

Moody’s also says that the outbreak “will intensify the focus of companies, investors and other stakeholders on environmental, social and governance factors, with the scrutiny extending beyond public health crises to other issues, such as climate change and social inequality” and that “entities demonstrating a stronger capability and willingness to address these risks will differentiate themselves from their peers”.

Don’t miss the Impact Investment and ESG Conference taking place on 15 October 2020

To learn more on the consultation and to watch recent webinars, visit www.esgsocialhousing.co.uk

RELATED